For a Small Group of Israeli Entrepreneurs, China Spells Opportunity

Israeli entrepreneurs are beginning to feel the attraction of the world’s second-largest economy, where an affordable market and a bubbling entrepreneurial atmosphere make up for language barriers

Ofir Dor | 19:00, 02.04.18

“For me, China is the land of opportunity," Israeli entrepreneur Fani Bar told Calcalist in an interview in March. "Only here can I open a bottle of wine at a restaurant and have someone walk up to me and order 300 bottles. In China, you never know where the next big thing will come from."

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

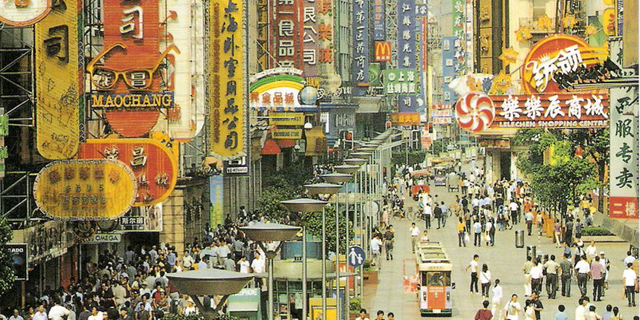

In October 2016, Ms. Bar, who first arrived in China to serve as the Director of the Israel-China Chamber of Commerce in Beijing, founded All in Wine, a Beijing-based wine marketing company, now employing a team of four and servicing hundreds of clients. China is the world’s second-largest economy, but the community of Israeli entrepreneurs there is still in its infancy. Language is a serious barrier, and without it, launching a business could be even more challenging than usual. Even the Israelis active in China often find it easier to pursue foreign clientele. But despite the many challenges, the Chinese economy offers unique advantages, from the relatively low initial investment required to malleable regulation and a bubbling entrepreneurial atmosphere. "Sometimes the bureaucratic systems work slowly, but your brain is always working here, and there are new fashions and ideas forming constantly,” Ms. Bar said. While most of Ms. Bar’s clients are foreigners living in China, “one Chinese client is worth 100 foreign clients," she said. "A Chinese client will not buy a bottle of wine for less than 700 yuan, while westerners typically spend 50-350 yuan.” Ms. Bar said that female entrepreneurs find it more challenging to run a business in China. “The Chinese do not see women as authoritative, and it is harder for a woman to earn the trust of the Chinese customer,” she said. "You need a lot of patience." “The problem is that China has a huge industry of wine forgery," Ms. Bar said. "Clients must know you and know that you are trustworthy before they buy expensive wine from you, and that takes time.” "Chinese buyers are sophisticated businessmen, even more than the Israelis," Ms. Bar said. "They can find a tiny loophole in a contract and use it to their benefit. They will bleed you dry asking for discounts. That is part of their conduct, and I respect that.” *** In 2008, after graduating with a degree in Economics and East Asian studies from the Hebrew University in Israel, Ilya Cheremnikh landed in Beijing with the purpose of continuing his studies of Chinese. But the outdated method in which Chinese universities taught the language frustrated him. So he decided to establish a language school and teach Chinese in a more contemporary and communicative manner. Today, his school, Culture Yard, has been active for eight years, employing 20 Chinese teachers. “I think China is a great place to start a business," Mr. Cheremnikh told Calcalist. "Prices did go up in recent years, but it is still relatively cheap to get started here." Mr. Cheremnikh had only 100,000 yuan, worth approximately $16,000, when he was starting out. "When I went to register the business, I received an unreasonable list of demands, including published textbooks, 500 square meters of office space, and at least two million yuan," he said. once he made clear that there was no way he could meet the requirements, a clerk recommended he register his business as a cultural center rather than a school. "Many people use agents, but I did it all by myself to save money, and it helped that I tried to speak Chinese,” Mr. Cheremnikh said. As part of the bureaucratic process, Mr. Cheremnikh had to become friendly with the neighbors. “I had to get their signatures to get my business approved. So I visited each of the neighbors to convince them to sign. At one point I gifted each neighbor with a crate of coke." Mr. Cheremnikh said he does not think he would have founded a similar school in Israel. “Beijing has an entrepreneurial air, and people encourage you to 'go for it.' In Israel, everyone will tell you how difficult it is to establish your own business and how everyone fails.” *** Israeli Aharon Dahan is a computer engineer. He met his Chinese wife in a language exchange meeting in Paris, where she was studying to become a pastry chef. Extreme competition in the Parisian patisserie scene sent the couple to Chengdu, in southeast China, where the two opened a patisserie. “All the machines for the business cost us 100,000 yuan here, compared with 100,000 euros in France,” Mr. Dahan told Calcalist. “Salaries are also low, 3,000 yuan a month. China has efficient delivery services that allow us to deliver easily and cheaply. You don't have that in France.” Mr. Dahan and his wife are now hoping to open up a second store, and are scouting for locations. “In malls, you are committed to keeping the place open 365 days a year, from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. It’s not easy,” Mr. Dahan said. *** 120 kilometers from Chengdu, Leshan is known for being the home of one of China’s most famous tourist attractions, the Leshan Giant Buddha. Israeli Omer Kapshuk, who also has a degree in East Asian studies, came to Leshan for love and settled there. In April 2017, he opened Sabra Cafe, a restaurant serving Israeli staples such as Shakshuka to local diners. The restaurant employs five. “I speak Mandarin Chinese, but here, everyone speaks the local Leshan dialect, so my first challenge was communicating with the construction workers building the place, and later with my employees," Mr. Kapshuk told Calcalist. "But it’s not just the language. Us Israelis, we tend to be very direct as far as giving criticism. My employees are a little surprised and sometimes offended.”

No Comments Add Comment