Opinion

Forcing a Subscription Model

While recurring revenue business models offer companies many advantages, they are not a one-size-fits-all strategy, writes venture capitalist Amit Karp

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

A subscription model is very natural for products that are used on an ongoing basis, such as a sales tool or an HR software license. On the other hand, there is a growing number of startups that provide services that are much less recurring in nature, yet are ‘forcing’ their customers to purchase a subscription instead of paying for a single use. The general logic behind pushing for a subscription is that the company can report revenue as Annual Recurring Revenue (ARR) and therefore benefit from ARR multiples when raising capital.

Let’s take, for example, a startup that provides a new way to do business card design. Naturally, a business card is not changed frequently and therefore is likely not a good fit for a subscription model. But let’s assume that instead of charging $50 for a single design, the startup now charges the same $50 as an annual subscription, allowing the customer to make several edits throughout the year. Most likely, many customers won’t need another business card after a year and will not renew the service. Some customers such as design studios may renew the annual license while others will just forget to cancel it. However, the result will be a high customer churn after the first year.

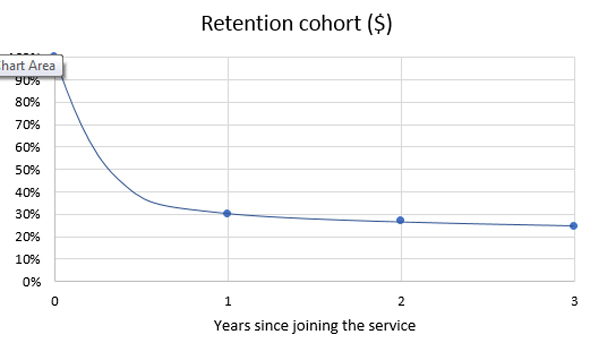

Let’s assume 30% of the customers who signed up for such a service renew their subscription after a year, and for simplicity, let’s assume 90% of the customers who stay after a year keep renewing the service every following year. The retention cohort will look something like this:

What this implies is that within a year the company will lose 70% of the revenue it generates from customers who signed up for the service today. If the company plans to double revenue next year, it will have to first fill in that 70% of lost revenue from its existing customer base and then grow another 100%. So for it to grow twice as much, it will need to generate 170% of new revenue instead of 100%. But this is still misleading — as the 170% of new revenue will also suffer from the same high churn and will result in much lower revenue down the line. I am not going to go over the math, but the ‘real’ new revenue number the company needs to attain in order to double revenue while taking into account the large first-year churn is 566%.

Put differently, this means that instead of adding 100% of new revenue every year the startup will need to add 566% to achieve the same growth rate. This is similar to trying to fill a leaking bathtub with a bucket that has a huge hole in the bottom. It is a daunting effort.

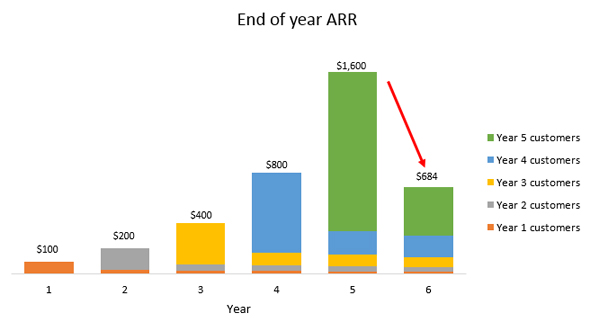

Now, let’s assume this startup doubles ARR every year for the first five years and then stops adding new customers. As you can see in the chart below, ‘real’ ARR in year six is only 42% of what was reported a year before:

What this means is that at some point in the future high-churn businesses will likely suffer from a stark decline in growth, which can have a terrible effect on the business. It is true that, for most companies, growth typically declines over time as revenue scales, but this decline is much more gradual for “regular” businesses and can be accounted for in their budgeting and plans. But companies who suffer from a high churn rate witness a very rapid decline in growth once they stop feeding the sales and marketing beast.

Many consumer and SMB subscription companies suffer from low first year retention, and it doesn’t necessarily mean these aren’t good companies. But for the above reasons, high-churn businesses should not be valued on the same revenue multiple that a ‘typical’ SaaS businesses attracts. These business models are just much more difficult to sustain over time as the bathtub keeps on leaking, and the hole in the bucket just grows and grows every year.

Amit Karp is a partner at the Israeli office of venture capital firm Bessemer Venture Partners, headquartered in Menlo-Park, California. This article was originally published on Medium.

No Comments Add Comment