American e-marketplace Groupon.com, which pioneered the group sales trend, is not doing so hot these days. A rising star in the U.S. tech industry, its 2011 initial public offering was the biggest Nasdaq IPO of an internet company since Google. Since then, the company’s stock dropped from $28 to under $3, and its famous business model, which required a minimal number of participants for a deal to be completed, has long been abandoned.

But while collective buying is a bygone trend in Europe and the U.S., it has seen surprising renaissance in China in recent years, if in a somewhat different style. Unlike Groupon, Pinduoduo Inc., China’s own harbinger of group buying, is currently one of Nasdaq’s hottest companies.

Founded in 2015 by ex-Google engineer Colin Huang Zheng, Pinduoduo is now China’s second largest e-commerce company after Alibaba, according to some indices. The company listed in July 2018 at $19 per share, and now, thanks to some excellent earnings reports, trades at around $43. Its market capitalization is $50.25 billion, much more than Groupon, which has a market capitalization of $1.66 billion, and even more than eBay, worth $28.59 billion. Pinduoduo, which currently operates only in China, recently made the list of China’s five largest internet companies, displacing veteran Baidu Inc., and even overtaking JD.com in terms of market capitalization and number of users.

Groupon, in its time, employed a business model that forced users to wait until enough people committed to a purchase before a discount was offered. Pinduoduo calls on its users to go out and find their discount partners themselves. Each product sold on the company’s app has two prices: one for people who choose to buy it on their own, and one—discounted—for those who add people to the transaction. In most cases, even one additional buyer is enough for the discount.

After users choose the discounted price, they are offered the option of sharing the deal via WeChat. They can also—and are encouraged to—add a personal voice message explaining why their friend should join in on the deal. If the contacted party cooperates, the transaction is completed and both buyers receive a lower price. Can’t find a buddy willing to pitch in? Worry not, Pinduoduo will partner you up with another user looking for a better deal.

China is no stranger to rags to riches stories, but Huang Zheng’s story is still one of the best. He was born in 1980 to working class parents in Hangzhou in East China, the same city where Alibaba was founded. Since a young age he excelled in mathematics, winning a scholarship to the prestigious Zhejiang University. During his degree studies, he interned at Microsoft’s Beijing offices, receiving 6,000 Chinese yuan (approximately $857 in current exchange rates) a month, more than his mother was paid at the time. Today, he is worth $22.5 billion and ranked seventh among China’s rich and in 94th place globally, according to Forbes.

Huang Zheng earned his master’s in computer sciences at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, before joining Google as an engineer. Two years later, he returned to China and worked at the company’s Chinese offices, at a time before Google was blocked in China and was still competing head-to-head with Baidu. But Huang Zheng quickly grew tired of Google’s centrelization, which necessitated its Chinese subsidiary to run all decisions by founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin. In one interview with Bloomberg, Huang Zheng said he had decided to quit the company after being forced to fly to the U.S. just to get Page’s and Brin’s signatures on a directive to change the color and font of the Chinese text on Google’s search results.

Following his resignation, Huang Zheng set up a marketing website for consumer electronic products and another company that helped brands promote their shops on Chinese commerce websites. But it was his third venture, a gaming company specializing in online role playing games (RPG), which proved especially essential to the future success of Pinduoduo—for games are a fundamental part of the company, and some say even the secret to its success.

Alibaba and Amazon, the undisputed rulers of the e-commerce industry, are functional and deliberate, a digital version of a supermarket. Their apps center around the search button, and their base assumption is that users reach for the app when they are looking for a specific product such as a book, a television, or a curtain. Alibaba and Amazon, therefore, emphasize their extensive product offering, with each search returning millions of results.

Pinduoduo, on the other hand, is more like a digital version of an Asian night market, or, according to Huang Zheng, a combination of Costco and Disneyland. Its product offering is relatively limited, and the search button is hidden at the bottom of the screen. Instead, the app centers around a personalized, Facebook-like feed of products intended to prompt the user to wander around various offers rather then focus on one specific product.

Groupon, whose first special offer was a buy-one-get-one deal in a neighborhood pizzeria in Chicago, specialized in selling vouchers for business: that is, luxury items. Pinduoduo, on the other hand, specializes in durable goods and basic daily products, from fruits and vegetables to clothes and tissues—one of the company’s biggest sellers. A monsterous batch of 40 tissue packages regularly costs 25 yuan ($3.57), but add a friend and the price drops to 19.7 yuan ($2.82). Having a cold has never been more economic. And since you still want this cold to go away, how about a package of 15 vitamin C-rich kiwis, at 18 yuan (approximately $2.57)? Got a friend who wants to fortify his or her immune system? You could both split the package for less than 10 yuan (approximately $1.5).

Pinduoduo also offers a bevy of sweepstakes, time-limited offers, and prize-yielding games intended to promote user-app interaction. A popular game, for example, asks the user to choose a specific tree, like a mango or a lemon, and water and fertilize it regularly. To supply it with water and fertilizer, users need to buy from the app, share offers, invite friends, or sometimes just open the app frequently. When the tree reaches its virtual maturity, the user wins a box of real fruits from their tree. Around 11 million people play that game daily. Another challenge asks users to add more and more friends to a deal to get the price down to zero, with a catch—the more people added, the smaller the new discount, and thus the harder it is to achieve a freemium.

Pinduoduo’s peak success has come at a time when the Chinese e-commerce market is showing signs of heading in a completely different direction. In recent years, analysts in China have repeatedly stated local consumers have started to look for higher-quality, more luxurious products. Alibaba and JD.com, China’s two leading e-commerce services, competed to see who could add more foreign luxury brands to its platform. But Pinduoduo has proven that there are plenty of local consumers interested in buying cheap, and even cheaper.

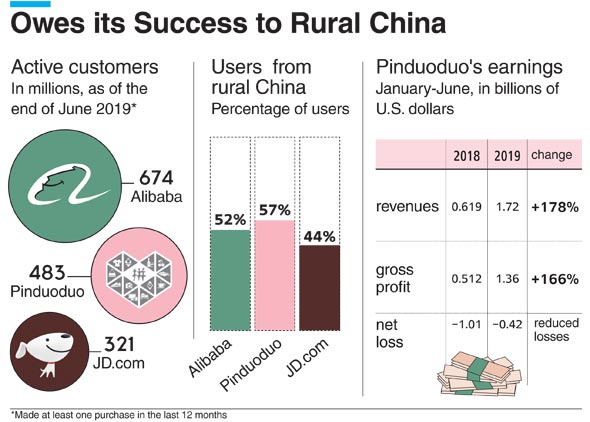

While sophisticated urban consumers initially ignored Pinduoduo, the app quickly became a sensation among China’s rural, less economically stable residents, those who lived in similar locations to Huang Zheng’s own childhood neighborhood. A survey conducted last year found that 57% of the company’s users come from cities and locations ranked tier 3 and under, compared to 52% of Alibaba’s users and 44% of JD.com’s. While those users earn smaller salaries, they also spend less on housing, leaving them income available for frivolities. According to official data, China’s rural residents spent $191 billion dollars on online shopping in 2018.

Unlike their urban counterparts, China’s rural residents have less entertainment options, leaving them more free time to collect discount buddies, participate in sweepstakes, and water virtual trees. Many of Pinduoduo’s users only became connected to the internet in recent years, and use the app not just for shopping, but as a way to spend their free time. China’s one-child policy turned the country into a rapidly aging nation, and the elderly retirees community proved especially loyal to Pinduoduo. They may not have a lot of money to spend, but they want to take part in the national pastime and, on the way, offer their family members discounts as a way to combat loneliness.

Many consumers were put off by the low quality of many of the products sold on Pinduoduo, and by the multiple counterfeit products offered on the site. But for Pinduoduo’s fans, those are just another level of the game—sometimes you’re duped, sometimes you win the jackpot. Even if you bought a dud, that’s not so bad, some users told Calcalist: shipping is free, and the prices are so low that a flop is never very painful.

Pinduoduo’s low prices have also made it one of the biggest winners now that China’s economy has started to slow down. Due to the trade tensions with the U.S., Chinese consumers are more careful with their money, and many more have started to look for discounted deals. As a result, Pinduoduo reached an amazing achievement in the second quarter of 2019: the company reported 483 million active users that made at least one purchase in the past 12 months (as of the end of June 2019). That achievement means Pinduoduo now has more active users than JD.com, which stands at 321 million, and it is second only to Alibaba, which has 674 million active users. JD.com is still ahead on revenues, as the average purchase made by its users is larger, but that is still an amazing accomplishment for a relatively new player in an industry that until recently looked like a duopole.

Even though Pinduoduo is a hot stock, it still faces significant challenges. The collective buying model saved the company on sales and marketing costs, as most of its early users came following personal recommendations and word of mouth. But to keep growing, Pinduoduo is now trying to break out of China’s rural areas and reach new audiences, including in large cities. As a result, the company’s expense per customer jumped to 1,465 yuan ($209) in the second quarter of 2019, almost double year-over-year.

At the same time, Pinduoduo is still dealing with constant and widespread customer complaints about faulty customer service and product quality issues. In April, the U.S. added the company to its list of counterfeit facilitators, due to its multiple intellectual property violations and counterfeit products. While the company is now trying to clean up its image by selling well-known brands such as Apple, it is still unclear whether people will want to buy their next iPhone from Pinduoduo. If that is not enough, JD.com and Alibaba both launched rival collective buying services in the past 18 months.

Additionally, like many companies that aggressively expand in a desire to conquer market share, Pinduoduo is still far from profitable, recording an operating loss of $271 million in the second quarter. To keep its prices low, the basic commissions the company charges from sellers are relatively low, and most of its income comes from payments retailers make to promote their offers on the app—much like the model used by Huang Zheng’s former employer Google. Under such circumstances, there is always the possibility that Pinduoduo’s cash will run out before it reaches profitability.

But the biggest danger facing Pinduoduo is that its now successful model of collective buying will no longer be of interest to consumers. If that sounds absurd, look at what happened to Groupon.

No Comments Add Comment