Opinion

After decades of being unappreciated, the pandemic could give distance learning a new lease on life

Covid-19 has brought the option of remote learning to the forefront of child and adult education alike, but whether it will rise to the occasion and become the new norm or be dragged down by ill-prepared professors and over distracted students is yet to be seen

Dov Greenbaum | 14:08, 09.06.20

This may be the best period in decades for technological wallflowers, namely, those innovations that have seemingly forever stood on the edge of the dancefloor, waiting for the right moment to become an integral component of modern society, but never, as of yet, finding that optimal entrée.

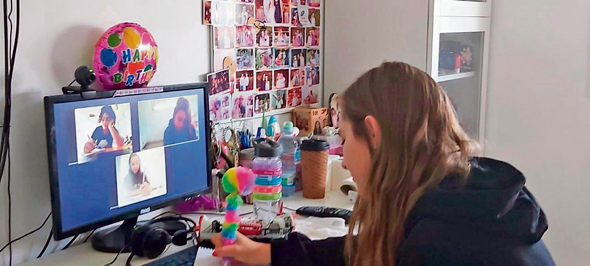

To wit, distance learning, although a hot legal topic at the turn of the century, never really found its niche, until now. With coronavirus (Covid-19) keeping many schools and academic institutions closed well into the next school year,

video conferencing tools have become a necessity in all areas of education, from elementary through university, distance learning now has the chance to strut its stuff.

However, if distance learning and the companies that support it, such as Zoom Video Communications Inc., which has become a Silicon Valley powerhouse

during this pandemic, are to remain successful, there are a number of legal issues that need to be addressed.

In the U.S., one of the major limitations placed by copyright law on distance learning was the initial requirement that teachers had to be face-to-face with their students to be exempt from potential copyright infringements ensuing from the unconsented use of copyrighted materials in their classes. Predicting the eventual growth of the online world, this law was changed in 2002 via the Technology Education and Copyright Harmonization (TEACH) Act.

The TEACH Act aimed to extend the standard in-person defense of infringement into the virtual world, provided certain conditions were met. Indicative of the importance of such a law, MIT, one of the first universities to jump into the fray, put 50 courses online that year as a proof of concept.

Copyright protections for e-learning were potentially further expanded this past March in a couple of important court cases in the U.S. First, a Ninth Circuit decision noted that the fair use defense to copyright infringement, an alternative to the somewhat onerous TEACH Act defense, covers teaching in both public and private settings, presumably, also online.

Also that month, in a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision, state institutions were exempted from copyright lawsuits altogether, unless they consented to be sued, under the longstanding doctrine of sovereign immunity. In the pertinent case, videos and images from the salvage of the infamous pirate Blackbeard’s shipwrecked flagship, Queen Anne’s Revenge, were published online by the State of North Carolina, off whose coast the boat ran aground in 1718. The ruling, which found earlier Congressional efforts to abrogate state sovereign immunity in copyright as unconstitutional, was in line with a similar 1999 Supreme Court case that found that Congress could not broadly legislate away the sovereign immunity rights of a state in patent lawsuits. As such, state-run public universities, which account for nearly 15 million enrolled students and professors in the U.S., may be similarly exempt from copyright lawsuits. This does not mean, however, that schools can rampantly infringe patents and copyrights with their new online courses. The court expressly pointed out that if states start acting like copyright pirates—pun seemingly intended—then Congress would be within its enumerated powers to draft a narrower law abrogating some of the sovereign immunity rights vis-à-vis copyright. Until then, continued sovereign immunity could be a boon to online educators who have found the TEACH Act to be too narrow in the exemptions it provided. Like much of copyright regulation, the inhibiting fingerprints of various interested stakeholders can be found within the TEACH Act. For example, it includes limitations on showing extended film scenes, which is a concession to the film industry. Additionally, the TEACH Act provides its broadest exemptions to only “nondramatic literary or musical work,” and provides no exemptions to supplemental materials that are not directly related to the lesson at hand. Professors that want to nevertheless rely on the TEACH Act exemptions can look to various online checklists for guidance. In addition to the intellectual property issues associated with distance learning, there are also substantial security and privacy concerns. In 2016, the Mirai Botnet, which remains an ongoing security threat even years later, exploited the lax security of thousands of cheap Chinese webcams to shut down internet access to millions. To accommodate those faculty and students that are on the wrong side of the digital divide, many academic institutions have provided the technological tools, such as cheap webcams, necessary to give and receive education at a distance. But this raises additional questions: if these devices are not properly secured, will these institutions be liable the next time a botnet exploits security holes in to take down the internet? What obligations do the schools have to their faculty and students regarding sufficient IT personnel to effectively prevent such attacks by helping their users with setting up devices? In addition to the gaping security hole, cameras in distance learning create privacy concerns for those individuals, who although they have no problem physically showing their faces in class, albeit now, with their faces safely covered, do not want to transmit to the world images of their home, the mess behind them, or even their own likeness. Practically, the former two can be rectified via default and custom backgrounds in programs like Zoom, and the latter concern can be dealt with through deep fake technology, at least by those with the necessary technical skill. Nevertheless, many students will still take advantage of privacy concerns and educators’ unwillingness to offend students as an excuse to keep their cameras off. These privacy considerations, however, need to be balanced with the educational considerations of the teachers, who often rely on reading the facial expressions of their audiences and need to know whether their students are paying attention, are lost, or are even physically present during the lecture. If a teacher cannot know that the student is even there because their camera is off, can they legitimately count them as absent? And, even if the student is present, knowing that the teacher cannot see them can lead to a lesser educational experience, as proven by generations of slackers sitting at the back of the classroom. Still, it is not so simple to demand that all cameras be kept on as the distance aspect of distance learning limits the educator’s ability to control the totality of the environment. Ought teachers be obligated to make sure that students are dressed appropriately? Can the students be counted on to prevent something inappropriate from entering the field of view? Even more problematically, a student could do something inappropriate during class that might not be allowed in the bricks and mortar classroom but might be legally defensible in their own home. In one documented incident, a Harvard Law School student brandished a gun during a Zoom class, which clearly put many of his classmates on edge. While Harvard prohibits guns on campus, can it also demand that a student hide their legal guns during an off-campus video class? Seeing an offensive image is not the only concern with video classes. It turns out that staring at a screen throughout a class can be exhausting for all involved, especially those participants that choose to exploit the opportunity to multitask. You know who you are. If distance learning over video conferencing is more exhausting and requires additional breaks to stay alert and focused, regulators and academic accreditors will need to assess whether time spent in class is equivalent to attending a virtual class and modify academic requirements to accommodate any differences. If learning remotely and learning in person are effectively equivalent, as many institutions might claim to justify their continued sky-high tuitions, then should someone who takes a diploma’s worth of Harvard online courses receive the equivalent of a Harvard degree? Can they put that on their resume, or is there some sort of je ne se quoi associated with campus life that differentiates an online education from an in-person one and justifies the cost and expense of campuses and campus-based learning.