World’s first AI satellite scans the Earth to find climate anomalies

The technology developed by Intel Movidius uses artificial intelligence to differentiate between images and predict future weather events, while eliminating the need for human analysis

With AI making breakthroughs in modern applications, from smartphones to drones, developers at Intel Movidius looked to apply that same technology in space. Movidius, a small Irish startup that was purchased by Intel in 2016, has worked with numerous agencies and companies to power the world’s first satellite that relies on AI in order to relay information about events on Earth, such as natural disasters, by utilizing a hyperspectral camera and smart technology.

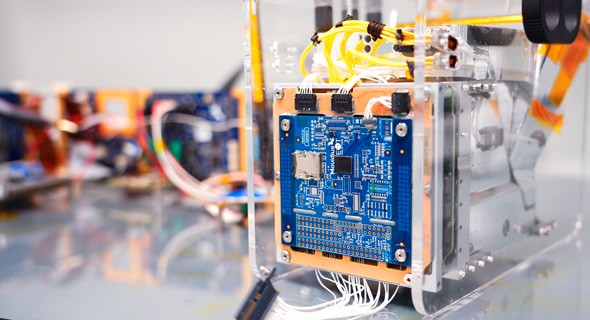

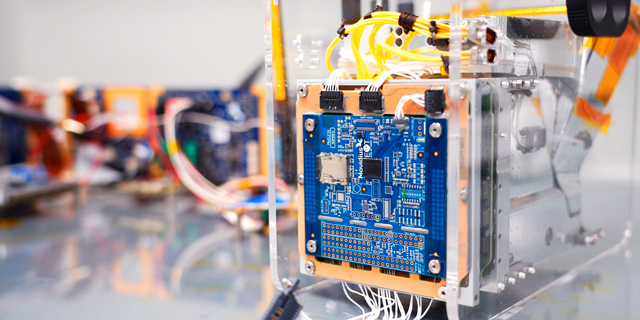

On Sep. 2, the partnership launched PhiSat-1, a satellite that contains a camera with hyperspectral and thermal capabilities and Intel Movidius’ Myriad 2 Vision Processing Unit (VPU), or “smart” chip. PhiSat-1 and a newer version, PhiSat-2 are set to monitor polar ice, soil moisture, fire activity, ships at sea, plant growth, and more. While initial data processing will be done on the ground for the first satellite, the process will be improved upon in the newer version as the AI system “learns” how to do so. Both versions will also test and improve intersatellite communications systems. Intel Movidius’ Head of the Technology Office and Chief Drone Pilot, Jonathan Byrne told Ctech in an interview about what makes this satellite so special. “The technology used is quite simple,” Byrne explained, adding that it is most commonly seen in drones, camera systems, and other devices that require low power consumption. In 2017, partners began to collaborate on the project, turning to Ubotica Tecnologías, a Spanish company which developed the board for space flight. To simulate the hazardous radioactive conditions in space, the chip was tested at the CERN Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest particle reactor located in Switzerland, and blasted with high energy particles, which it managed to withstand. “Because transistors are now so small, it makes them very vulnerable to ionizing radiation,” Bryne said. Chip design for space applications is very limited because it requires high quality, complex hardware, and current VPUs in space are 20 years behind technology-wise, because they are highly expensive and take several years to develop, Bryne explained. “The Myriad 2, isa commercial off-the-shelf chip. We took a device that is present in 99% of drones and rather than spending all that money toward developing the technology, utilized existing technology and tweaked it,” he said.

“Our processors use low-powered chips for satellite operations research into future applications for this technology, and we have shown that it can work in space as well,” he said. The hardware is designed to run on multiple satellite networks. The low-powered technology has other advantages, for instance it doesn’t overheat like most devices in space do, while being energy-efficient. The European Space Agency (ESA) had originally developed the LEON4 core processor, and open sourced this device for others to use. Movidius used this design and then built their improved system around it. Byrne added that most satellites today now generate massive amounts of data. Like most smart device manufacturers today, developers are looking to miniaturize them and also reduce their costs. The AI works to monitor the images and eliminate the need for human analysis. PhiSat-1’s spectral camera is capable of differentiating between clouds and other data such as unique occurrences on Earth, like forest fires, and deciding which information must be sent back to Terra Firma. It uses artificially engineered neural networks to process the data, and reduces the camera’s bandwidth by 60%, making it cheaper to produce as well.

“Our satellite looks at images as they’re generated in space and decides whether to send us them or not,” Bryne said, adding that this could be used to predict various events. Currently, the satellite will be working on detecting forest fires, low-flying planes, and clouds. Additionally, it can update other satellite networks as well.

With the drive to develop low cost CubeSats, or miniaturized satellites, prices will go down to around $50,000, and cameras will size down as well, multiple versions can be sent into space, and monitored routinely.

Movidius chips are designed in Leixlip, Ireland, the only location where Intel produces semiconductors outside Israel and the U.S.