“We needn’t be afraid of mutated British Covid-19 strain,” says senior Israeli researcher

“Scientists identified over 10,000 mutations in the coronavirus, and the existing vaccines can identify them and respond accordingly,” says Prof. Michal Linial

Yoghev Carmel | 12:46, 22.12.20

“There isn’t any need to be afraid of the mutated coronavirus (Covid-19) strains that were discovered in the U.K. They aren’t more dangerous than the existing strain and the existing vaccines won’t be any less effective against them,” Prof. Michal Linial told Calcalist. She researches coronaviruses and is a professor of molecular biology and bioinformatics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

“Scientists have already mapped thousands of strains of the coronavirus and we already know that currently there are over 10,000 different mutations,” she added. “This specific mutation we had already mapped in September, but back then it only appeared in small numbers. Somehow, it reached large numbers in London. We didn’t expect this mutation to have so many differences to the original, and without this scientific surprise, it wouldn’t even be worth mentioning. The existing vaccine knows how to identify mutations in the virus and respond accordingly.”

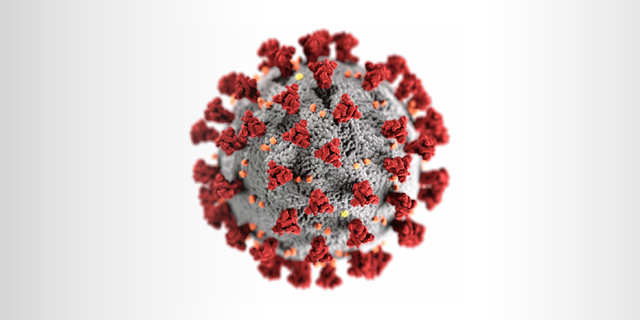

“The existing Covid-19 vaccines will help our bodies produce the infamous coronavirus spike protein. (After the body’s cells make copies of the protein, they eradicate the genetic material from the vaccine.) It is a single protein out of many that are found in the virus. Imagine that this protein is a single sentence in a book with thousands of letters, and I’m telling you that in the entire book there are some typos. If you’d read the book, would you still understand what it means? Probably. Every time that the virus splits and multiplies, it can cause a change in its genetic code. Scientists have already mapped out thousands of different versions of the coronavirus, and we already know that there are around 10,000 different mutations. These different versions of the virus already existed, but their sequence with differences, or typos to extend the analogy, didn’t exist.”

Why do we need two “booster” shots of the coronavirus vaccine?

“The immune system works like an identification and recognition system. At the first stage, the immune system recognizes the “enemy-invader” and it takes time to respond. That’s why we send people who have been exposed to the coronavirus to remain in quarantine for two weeks. So, the second booster shot is for the immune system to prevent the body from entering a state where it ‘forgets’ what it previously recognized. That reminder activates the immune system’s response. I estimate that in the future, companies will make an effort to provide the vaccine in a single dose, without harming the vaccine’s effectiveness. Now, companies aren’t trying to optimize the vaccine, neither monetary-wise or in terms of its lasting-time or amount, rather they are doing what is right, and deploying it as quickly as possible.”

Do you think coronavirus (Covid-19) vaccines will fall under the government healthcare basket that everyone is entitled to receive, like the measles vaccine?

“It’s still too early to talk about that. If we look at the SARS virus for example, which is similar to the coronavirus, two years after its initial outbreak there wasn’t a single instance of it anywhere in the world. It could be that if we manage to eradicate the virus, it will disappear like smallpox. No one gets vaccinated against the Ebola virus, even though the virus still exists because it's only found in certain places. The Ebola vaccine is reserved for people who fly to African countries, where the virus is rampant. It could be that the course of evolution will make the coronavirus (Covid-19) weaken, like its relative, the flu virus.”

Science is already familiar with other viruses, so how is it that the coronavirus caught us by surprise?

“Since March, we conducted a scientific test and asked what would happen if we had excellent antibodies that could treat SARS. Would they be effective against Covid-19? The answer is a resounding ‘no.’ The reason we’re seeing these small changes that have evolved over time between many strains of the coronavirus (Covid-19) is that the protein’s active recognition site has been altered and now the virus uses a different strategy to enter the body. Every virus, during its evolutionary course, creates an optimal pathway to enter the body. We must remember that the next virus will come along someday too. There is an infinite number of viruses, and all we need in order to prevent the next dramatic outbreak is to ensure that different countries have excellent plans for how to combat the virus and that the human population won’t be contaminated by wild animal viruses. It’s also important to strengthen vaccine technology so that we can easily engineer an antibody. I estimate that if pharmaceutical companies will need to develop a Covid-24 antibody, for example, it will take them two weeks and not half a year. We must ensure that our accumulated knowledge on this project will be safeguarded and not go to waste.”

As someone who has worked on developing a drug to treat the coronavirus are you disappointed by the new vaccines? It’s possible that people will not even need a cure.

“That would be fantastic. It would be the happiest thing that I could think of for my career. There aren't any scientists out there who don't dream of their research one day becoming obsolete, because that would mean the disease had disappeared. We aren’t financial people who are looking to make an exit. We want the entire world to be healthy, and our way to do so is by shortening processes.”

Where does the research stand today on developing a treatment?

“Some of our research is in the field of bioinformatics, meaning that we are looking at the genetic sequence, and drawing conclusions from there. For example, today we’re trying to take coronavirus proteins and encapsulate their mRNA into a human cell. We want to know how a virus can succeed in generating a serious lung disease, while on the other hand, it can also cause blood clotting, skin diseases, or neurological diseases. We’re trying to decipher the problem, and see what the virus does inside the human cell that causes such a serious shutdown of these major systems. We’ve already succeeded in discovering that the virus can shut down a cell’s system, even though its job is to cause an emergency distress response. The virus ‘removes its battery’ so to speak, and cells continue to work like normal. The entire intercellular communication system is lost because the virus manages to silence the only system that is working to combat it. We are very far away from drawing conclusions, mainly because it’s a virus that works in a very clever way. I’m surprised by it every day.”

You won’t miss all the attention that has been showered on you and other scientists over the past year?

“What motivates me, just like most scientists, is intellectual and scholarly curiosity. Our work is based on our curiosity, and once in a while, something happens and people need us. If the human population will return in another year to where it was previously, when science was pushed to the side as something amusing for professors to busy themselves with, then we’ve missed the whole point. It isn’t because science has solved the problem and created a vaccine, but rather because as in everything in life, like politics, for example, sometimes the world deserves to get a failing grade. As scientists, we are trying to take this lesson and make science accessible to the entire world. We need to take personal responsibility for that.”