Interview

"Israelis have the desire to feel like they are the smartest ones in the room. But that hinders learning"

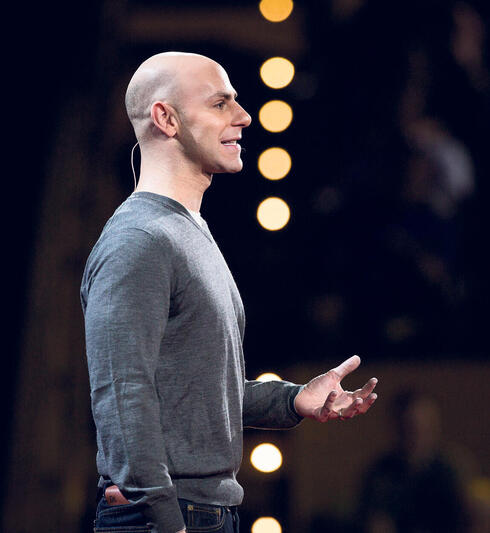

Prof. Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist who has advised top executives from Elon Musk to Jeff Bezos, provides an eye-opening explanation as to why it is so difficult for us to admit our mistakes and how we can fix it

In the winter of 2018, Prof. Adam Grant proposed a revolutionary experiment to a group of Fortune 500 CEOs: on Fridays they would allow their employees to work remotely. Grant explained that many studies have shown that hybrid work contributes to creativity and efficiency, but all the CEOs, without exception, refused. "They saw it as a Pandora's box and thought: if the experiment fails, they won't be able to turn back the clock," Grant tells Calcalist. "Of course now that we have all participated in this experiment, because of the coronavirus, they were forced to open the box, and discovered that there is a lot to learn from what is inside. Bottom line, whoever is afraid of experiments, and does not question the way things are done, will never learn anything new - and this will prevent growth, development and change.”

Grant is not used to such blatant rejections. When he speaks, people usually listen: At just 41, he's a professor of organizational psychology at the Wharton School of Business; Consultant for giants such as Google, Facebook, Pixar, IBM, Goldman Sachs, the NBA, the United States Army and the Gates Foundation (to name a few); A successful writer who wrote five New York Times bestsellers, which were translated into 35 languages; host of a popular podcast, "WorkLife", which deals with ways to enjoy work more, and was dubbed "the Porsche of podcasts" by Inc magazine; and a popular TED speaker whose talks have garnered tens of millions of views.

However, in his experimental proposal for hybrid work Grant's personal charm and experience did not do the job. Surprisingly, he points the blame at himself. "I think that if I had the understanding in 2018 that opening 'Pandora's boxes' is essential for the growth of organizations, maybe I wouldn't have preached so much to those CEOs about the solid evidence we have about the success of remote work, and I wouldn't have gone and accused them of being ridiculous to think that their organization is different from all the others that have been studied," he says.

What would you have done differently?

"I would approach this much more scientifically and say, you know what? You have an interesting hypothesis, and I'm really curious to find out how this would play out in your world. What evidence would convince you that you're wrong and how could we gather that evidence together? And I didn't see that the mistake that I made was that I basically fell into the traps that I criticized in my book."

“Prosecutor”, "Preacher" and “Politician” are of the key concepts in Grant's latest bestseller, ‘Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know’, whose main message is that intelligence is not just the ability to learn, but also the ability to cultivate mental flexibility. The problem for most of us is that, in conversations with others, we oscillate between being in the position of the preacher - delivering sermons to defend and promote our ideals; The prosecutor – who finds flaws in the logic of their interlocutor and uses them in our arguments to prove others wrong; and the politician - who embarks on campaigns of persuasion and lobbying that will win the support of our constituents. Instead, Grant encourages us to engage like scientists, who strive to find the truth through experiments that test hypotheses, thus accumulating information.

What is the problem with being a preacher, a prosecutor or a politician?

“Many people are too interested in proselytizing their own views, attacking other people's views, or basically only listening to people who already agree with their views, and that stops them from being open to changing their minds. I think if you can get out of those mindsets and into the mindset of thinking more like a scientist, that's when we start to see the skillset come into play. A lot of the skills are the basic skills of critical thinking that we were supposed to learn in school.

It's not that hard to ask, I wonder when this hypothesis is false, or who are the people who disagree with me, not for political reasons, but because they are also interested in finding the truth and they have, perhaps, different knowledge than I do, or different experience than I do. But for me, the mindset is where the skills break down, because it doesn't matter how much time we spend teaching people to think like scientists, if they're not motivated to do it, then those skills basically collect dust.”

Suppose they gather dust. The Fortune 500 companies, which did not respond to your proposal, managed without it. Whereas a change of opinion may be perceived as a sign of weakness in leaders. Why is it so important to develop such a skill set in the first place?

"Because many of the ideas that made people and organizations successful at one point in time caused their downfall at a later point, when the world changed. Take Blackberry for example: founder Mike Lazaridis was absolutely right when he assessed that people wanted a device to send work emails in pocket size. He was also absolutely correct when he assessed that consumers want keyboard keys. However, his failure to change his mind (Lazaridis consistently and emphatically refused to equip the BlackBerry with a touch screen, even when the iPhone had already captured a quarter of the smartphone market, R.D.) ultimately resulted in his company, which dominated the market, failing.

"And I think this is true across domains: too many strategies and practices were invented for a world that no longer exists, and the slower you are to admit that you may have been wrong, the longer it will take you to get it right. In a world of accelerating change, this is a very short-sighted and risky way to operate".

The Inner Dictator Trapֿ

Grant grew up in a suburb of Detroit, Michigan, the son of a lawyer and a teacher. He graduated with honors from Harvard University, and completed a master's and doctorate in psychology from the University of Michigan. He also had time to dabble as a magician for no less than a decade - an occupation that made him an outstanding lecturer ("I'm an introvert, but I received golden advice from someone who used to be my mentor: to release the magician in me," he shared in one of his many Ted talks, "so I turned teaching into a live performing act").

In 2013, around the time he released his first book, "Give and Take", was when Grant became a star outside the academic community. An extensive profile in the New York Times made him famous overnight. “It led to many more requests for my time (my inbox was flooded), but also opened many doors—for new research projects as well as sharing knowledge more broadly through writing and speaking”.

Today he lives in Pennsylvania with his partner Alison and their three children, and teaches, as mentioned, at Wharton at the University of Pennsylvania - where he set a record at the age of 26 when he became the youngest tenured lecturer. His research deals with motivational factors at work, studying the psychology of giving and helping others, developing feelings of meaning and job satisfaction, initiative and leadership.

One of the qualities that made Grant such a popular lecturer is his candor when sharing the many mistakes he made in his life. One of them was his decision not to invest in Warby Parker, the trendy glasses company that was founded in 2010, and now, a year after it was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, is valued at $1.58 billion. Another mistake of his turned out to be even more fatal: "Facebook was established five years after Harvard's first social network, which was abandoned,” he writes in the prologue of "Think Again". "The students who founded the original internet group feel regret to this day for not sticking with it. I know this as someone who was one of them... Since those days, rethinking has become a central part of my sense of self."

Grant even admits out loud not only his mistakes, but his character flaws. For example, in his book he uses the concept of the "inner dictator": "I wish somebody had taught me this (as a child)," he says now. "I remember in college, I read the classic paper on the totalitarian ego and I still didn't really understand, I thought to myself 'hmm, I hate it when other people do that, it's so annoying'. But it wasn't until much later in life that I realized that this a lot of what annoyed my friends about me growing up was that same inner dictator."

How did this feature manifest itself?

"It started when my nickname was 'Mr. Facts' as a kid because I was always correcting my friends, at first about baseball statistics, and then it branched out into other sports. When I was 12 years old, I argued with a friend on the phone about a quote from a movie, and I was so convinced I was right, I told him: 'Okay, I'll just play the film here, I have it recorded.' And when I played the film and found out I was wrong, I just couldn't admit it. I couldn't get the words out of my mouth.

"Today, with the advantage of perspective, I realize that at the time, admitting a mistake was a serious threat to my ego, and placed a big question mark over my intelligence, my memory, and the things that were really fundamental to my sense of self. At the time, I preferred to define myself as an 'expert', and today I identify more with definitions such as 'researcher' and 'curious'. Now I am more interested in finding the gaps in my expertise so that I can continue to grow my knowledge."

You were misled about the frog

In "Think Again" Grant debunks several common myths about decision-making, mainly the myth that it is better to trust the initial conclusion we have formed, assuming that it is often the correct one. Even Kaplan, the largest test preparation company in the United States, has warned students in the past "to be very careful when you decide to change an answer. Experience shows that many students who change their answers change them to wrong answers." However, 33 studies conducted on the subject and mentioned in the book found that the opposite is true - most of the corrections of the subjects' answers replaced wrong answers with correct answers.

Another myth that is debunked in the book is the well-known parable of the frog, according to which if you throw a frog into a pot of boiling water it will immediately jump out, but if you throw it into lukewarm water and gradually raise the temperature, it will die. In practice, says Grant, a study on the subject found that when a frog is thrown into a boiling pot, it will be badly burned and may or may not escape. However, the situation of the frog in a pot that gradually boils is better - because as soon as the water reaches a temperature that will disturb it, it will jump out. "It's not the frogs who fail to reassess the situation," Grant writes. "The failure is ours. Once we hear the story and decide it is true, we rarely bother to question it."

What these myths have in common is that they both stem from excessive and blind self-confidence. In order for us to develop and grow, Grant explains, we must find the optimal point of self-confidence, somewhere in the middle between blind arrogance and crippling doubts and feelings of inferiority. He calls this point "confident humility" - it is a belief in our abilities that comes with the recognition that we may not have the right solution. Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister of New Zealand, is the perfect embodiment of confident humility, according to Grant. "She simply said to the citizens of her country: Look, we don't know yet how to best to fight Covid.s we gain new information, and as the science evolves, we’re gonna change our policies and plans accordingly."

This is the exact opposite of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who are full of themselves to the point of bursting. This is the kind of leadership we were raised to admire.

"I think you’re right," he laughs. "I wouldn't describe Musk as a paragon of humility. In 2018, he even tweeted: 'If I'm a narcissist, at least I'm a useful one,' he added a wink that indicates at least some self-awareness. But around that time, I met him for a few dinners, and I was surprised to find that when talking to him about his very specific goals, you can see that beyond the veil of his self-confidence there is a lot of depth in him."

For example?

"I once asked him what he thought the chances were of humans reaching Mars in his lifetime. And he answered: 'I used to think the chances were 8-9%. But now, after we've made all the progress at SpaceX, I think the chances are...' — and at this point he smiled, and his eyes opened and shone, so I thought to myself, 'Okay, here it comes' — 'Apparently 11%.' I said to him: 'Sorry, I don't understand. We went from 9% to 11%, why are you so excited?'. And he answered, 'That’s double digits, it's a big deal!'. So he doesn't publicly externalize this side of him, but if you press him a little, you see that he has a balance between faith and depth. Also, this is something I heard a lot from the engineering teams that work closely with him."

In "Think Again" you actually identify patterns common to confident humility and impostor syndrome. How is that possible?

"For some people, imposter syndrome just becomes debilitating death—people walking around the world thinking they're an actual fraud, that they've never been good enough for any job they've ever had, and that it’s only a matter of minutes until everybody finds out. But a recently published study shows that the typical impact of impostor thoughts like, 'I think people overestimate my worth,' don’t have consistent costs and actually have consistent benefits: we work harder, longer. , and smarter because we know we don't have all the answers—and that makes us more open to learning from the people around us. When you think about it this way, you realize that those moments, when we feel like imposters, enable a meeting between humility and confidence, where you can say: I know that I don't know everything that is needed to deal with a certain situation effectively, but I believe that I am capable of learning it.

"There's a comical paradox in imposter syndrome: on the one hand you don't believe in yourself, and on the other hand you stronglybelieve in your own judgment of yourself. Wait a minute, you can’t have it both ways! If you have no idea what you're doing, then you're in no position to judge whether you know or don’t know what you're doing. And if there are some people who have high expectations of you, and are objective or at least less biased, then it probably makes more sense to trust them than yourself."

That's a bit of a Catch-22, isn't it? If I overcome the impostor syndrome and start believing in myself, I might also lose my confident humility.

"Yes, it's a tightrope walk. I like to distinguish between doubting ourselves and doubting our tools. In order to maintain humility, we don't always have to doubt ourselves, and ask if we're smart or have skills - that's just a way of harming ourselves. What I do encourage people to do is to say: OK, I believe I'm smart, talented, and a great learner, but I'll never know everything. There will always be gaps. In order to achieve my goals, I have to keep an open mind and examine my methods and habits. That's where the best combination is obtained, of motivation and learning."

A true friend will criticize you honestly

How do you implement rethinking? Give us some tips.

"I would start by creating a list of ignorance. If you make a list of topics that you have no idea about, then when they come up in conversation, instead of diverting to topics that you understand, you will remember that there is an opportunity to learn from the people around you, who have knowledge that you do not have. This is one of the problems I have with the desire to always be the smartest person in the room which is very much alive and wellin Israel and the United States. Because, if we all just focus on who is the smartest in the room, we will never learn what each of the people present in the room is smart about."

Related articles:

What else?

"The second tip is to surround yourself with a challenge network: a group of critics you trust who will hold up a mirror to your blind spots. Everyone has a support group - people who stand by us and always encourage us. Your challenge group does the opposite, and you need to make it clear to its members that there is no conflict between their honesty towards you and their loyalty to you as friends. You should tell them: this is the role you play in my life, and it is no less important than encouragement. For me, honesty is the highest expression of loyalty, and the more honest a person is with me, the more I will value their feedback, because I know they are trying to help me learn and improve.

"The third tip is to make time for rethinking: most of us already know that it is important to dedicate time to learning and thinking outside our fields, and to talking with people outside our industry, but time spent on rethinking is something else. It is a time when we examine our opinions and decisions from the past and ask: Are we still at peace with them? Or maybe our knowledge and thinking have evolved further from there? Now is the time to turn to the challenge group and ask: Based on the last few weeks and months, is there anything you think I should rethink?

"It should be a routine that you commit to in your schedule in order for it to happen. Among other things, because when we reserve time for rethinking, it's much easier to deal with than someone telling us to rethink something - simply because you're saying I want to do this as opposed to maybe somebody dragging you kicking and screaming to force you to do it.

"My last tip is to schedule general checkups for your career or life in general, just like you schedule an appointment with the dentist. Studies show that couples who do a general checkup on their marriage when everything is fine, usually have a more resilient relationship. Because guess what? It's easier to rethink things when you're not angry at your partner and not in the middle of a fight. So this idea applies to everything in life, whether it's your career, marriage or anything that's important to you - it's worth asking yourself once or twice a year: Have my goals and views evolved? How have the people around me evolved? What would I like to rethink instead of being stuck to old routines, that were maybe created by past versions of myself?"