To succeed in defense-tech, Israeli startups must stake their claim in the US

The acquisition of Paragon by American investment firm AE, which could reach almost $1 billion, is another testament to how geopolitical dynamics push Israeli companies to establish a stronger American presence or sell out to U.S. firms.

The exit of Israeli offensive cyber company Paragon, which could reach around $1 billion, marks a striking finale to 2024, a year that saw an unexpected resurgence in Israeli tech exits. The total value of exits in Israel's high-tech sector surged 78% compared to the previous year, reaching $15 billion. The Paragon deal, along with Perception Point’s $100 million sale to Fortinet last week, suggests that this figure could climb further before year-end.

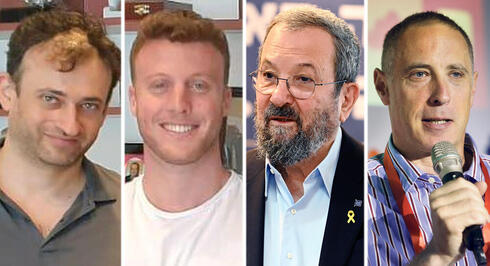

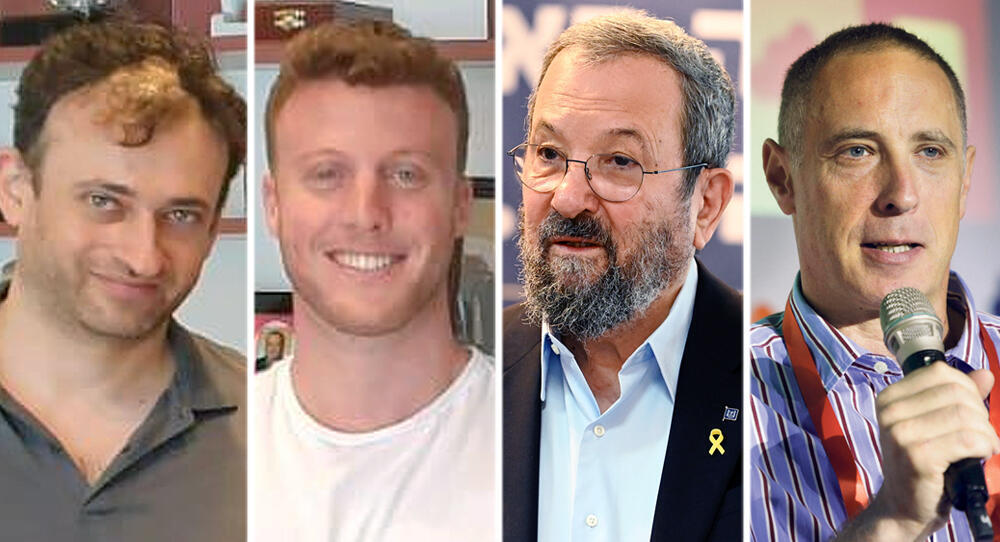

Founded in 2019 by alumni of Israel’s elite Unit 8200, including its former commander Ehud Schneerson, and backed by former Prime Minister Ehud Barak, Paragon has solidified itself as a leader in spyware technology. The company recently secured approval from Israel’s Ministry of Defense to sell itself to U.S. investment fund AE for $500 million in cash, with a potential for the deal to grow to around $1 billion if Paragon meets certain performance milestones in growth and profitability. Insiders close to the deal indicate that these goals are well within reach for the profitable company, which already generates over $100 million in annual revenue.

The sale will bring significant returns to Paragon’s founders and employees, who collectively own 30% of the company. CEO Idan Nurik holds a 6% stake, co-founder Igor Bogudlov owns 3.5%, and Schneerson retains 10%. Barak, as an early investor, owns 3.5% and is set to earn several million dollars from the transaction. Other beneficiaries include major venture capital backers, including Battery Ventures and Red Dot.

Despite its rapid success, the question arises: Why sell now, when Paragon is profitable, growing, and not under financial pressure? According to senior sources familiar with the company, the answer lies in the unique challenges faced by Israeli defense tech companies in securing contracts with Western defense systems, particularly in the U.S. While Israeli firms often establish American subsidiaries, that is no longer sufficient. Paragon’s leadership recognized that to scale its operations and compete for federal contracts, it needed to be under full American ownership.

Related articles:

This realization reflects a broader trend in the Israeli defense tech ecosystem. Cellebrite, a company known for its forensic software that extracts data from encrypted devices, recently acquired an American company to meet similar regulatory and operational challenges. For Israeli firms like Paragon and Cellebrite, securing a foothold in the U.S. defense market requires adapting to geopolitical and bureaucratic realities.

Paragon’s flagship spyware, Graphite, is reportedly capable of extracting data from encrypted platforms such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and Signal. The company strictly limits its sales to democratic nations and refuses deals with regimes that pose risks of misuse, positioning itself as a more ethical alternative to competitors like NSO Group, Candiru, and Intelexa, which have faced international scrutiny and blacklisting by the Biden administration.

The buyer, AE, is an American investment fund specializing in infrastructure and security. AE’s strategy revolves around building a robust defense platform by acquiring high-performing companies like Paragon. The fund had previously purchased U.S.-based Red Lattice, a cyber-consulting firm with strong ties to American security agencies but limited growth potential. By integrating Paragon’s technology, AE aims to create a scalable defense tech entity capable of competing globally and, potentially, being acquired by giants like Lockheed Martin or General Dynamics in the future.

Paragon’s exit also signals a broader shift in the Israeli defense tech landscape. Last week, Tel Aviv hosted a major Defense Tech conference, drawing significant international attention, including rare visits from European and American representatives. Discussions at the event highlighted the growing demand for Israeli innovations in cybersecurity, AI, and surveillance tools. However, the central question remains: Can Israel cultivate large, globally competitive defense tech companies, or will these firms inevitably shift to American ownership to achieve scale and influence?

The Paragon deal exemplifies both the promise and the challenges facing Israeli defense tech. While it underscores the sector's innovation and profitability, it also raises concerns about the ability to retain these companies as Israeli entities in a global market increasingly shaped by geopolitical considerations.