Analysis

When the chips are down: A US-China cold war is brewing

At a time when demand is at its peak, the Chinese trade in semiconductors is actually shrinking. The reason: the reaction of the global industry to American sanctions. While China is trying to find components that are not included in the boycott and continue production, the American government is subsidizing the establishment of advanced factories and reducing dependence on Asia

Something unusual is happening these days in China. Global demand for semiconductors is at an all-time high, with the pressure that began during the pandemic only now beginning to be released and the supply finally meeting the demand. In China, on the other hand, between January and April, the number of chips imported into the country fell by 21.1% to a total value of $146.8 billion, and exports fell by 25.6% to $105.6 billion. The reason: not the lack of demand, but rather a reaction of the global industry to the American sanctions, especially in South Korea and Taiwan, which makes it clear: we are in the midst of an economic cold war.

During the 20th century's Cold War, two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, conducted a nuclear arms race with the aim of building the largest arsenal of atomic and hydrogen bombs, a deterrent against a possible nuclear attack by the other side. 32 years after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the conflict, today the world is again in the midst of a cold war. The Soviet Union is being replaced by the People's Republic of China, but fundamentally it is a struggle with similar characteristics: competition for economic, social, ideological and technological dominance.

And as in the first cold war, here too there is an arms race, with bombs being replaced by the most significant weapon of the modern economy: chips. And each side in the struggle using its own strategy and tactics to make sure it doesn't get left behind.

Traditionally, the USA is the hotbed of intellectual property for the chip industry. Players such as the British ARM have helped to diversify intellectual property to other countries, but the field still remains controlled by the Western world. At the same time, centers of production of sophisticated chips have grown in East Asia, mainly in South Korea (Samsung) and Taiwan (TSMC), where the most complex and expensive chips are made. China's role has mainly been in the production of less sophisticated chips, a necessary part of the industry but not the most prestigious or profitable.

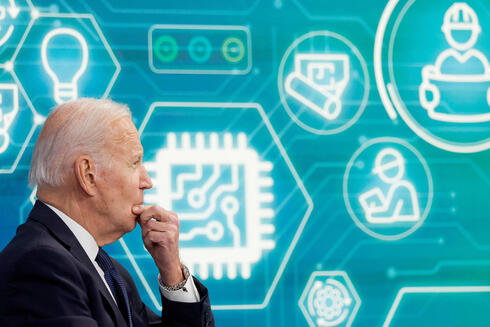

China, for understandable reasons, sought to strengthen its capabilities and began investing in new factories for the production of advanced chips in order to achieve independence in the field. One that would not only allow it better financial control over its future, but would also ensure the supply of sophisticated chips to its domestic arms industry. President Joe Biden's administration was also quick to understand the importance of dominance in the chips sector, and last October published a series of strict restrictions that cut off China's access to Western tools and workers, which are needed in the production of the most sophisticated chips. The global chip war began.

According to the American restrictions, citizens are prohibited from helping Chinese companies build chip technology above a certain level of sophistication - much broader restrictions than those of the Trump administration that focused on specific Chinese companies such as Huawei. The effect was immediate. American workers immediately left, and American suppliers, as well as European and Japanese ones, stopped supplying products and services. Samsung and TSMC, which previously invested in the development of the chip industry in China, directed their financial resources to other countries. TSMC, for example, is investing billions of dollars in building an advanced chip factory in Arizona thanks to subsidies from the U.S. government.

The result was an acceleration of Chinese efforts to expand and upgrade chip operations, with huge investments in local companies, especially those developing less sophisticated chips. At the same time, China is trying to build advanced chip manufacturing capabilities based on older parts and devices that were not blocked by the U.S. "China's goal is to de-Americanize the supply chain," Paul Triolo, Senior Vice President for China and Technology Policy Lead at Albright Stonebridge Group, told the New York Times.

This is directly supported by the state, which activated a dormant investment fund for this purpose. In February, the fund poured $1.9 billion into the local chip company YMTC, and invested additional sums in equipment and material suppliers. The city of Guangzhou has allocated $21 billion to the local chip industry and to projects that promote the replacement of Western chips with Chinese ones.

Related articles:

The Chinese industry has huge gaps to close. As of today, it is responsible for less than 1% of the output of the most advanced chips that are under U.S. sanctions. However, experts estimate that reducing foreign involvement in the Chinese market will create opportunities for local companies.

The U.S. has its own challenges in the arms race against China. When it comes to intellectual property it is indeed a world leader, but its production base is very limited. This intellectual property is important, but without production capabilities it is not worth much. And when the global production bases of advanced chips are very close to China, when the country even claims that Taiwan should be part of it, the need for local production is particularly important. In its efforts to strengthen the country's capabilities in this field, the Biden administration is targeting investment mainly in a relatively innovative technology known as Chiplets.

Traditionally, the main improvement in the performance of chips is done by shrinking their electronic components, so that more power can be squeezed into less space. About a decade ago, the American company AMD began testing a radical idea for its time: instead of designing one large chip that consists of a large number of tiny transistors, create smaller chips that are packaged together and work as one. The idea has distinct advantages - small chips that are cheaper to manufacture and package together can provide better performance than one large chip.

This technology is at the center of the Biden administration's policy to revive chip production in the U.S. Today, the U.S. is responsible for producing 12% of the global chip supply, but only 3% of chip packaging. The huge subsidy package for the sector in the amount of $52 billion approved by the Biden administration last summer is aimed, among other things, at encouraging the establishment of chip packaging factories. "As chips get smaller, the way you arrange them, the packaging, becomes more and more important and we need to do it in America," Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said in a February speech at Georgetown University.

The market is already responding to the huge stimulus package. Integra Technologies has announced plans to expand its Kansas plant at a cost of $1.8 billion, contingent on receiving a federal subsidy. Amkor Technology, most of whose packaging plants are currently located in Asia, is in talks to establish a plant in the U.S.

And yet, the task is not easy. "Even with a subsidy, concentrating all the components needed to reduce American dependence on Asian companies is a huge challenge," Andreas Olofsson, who previously led the Defense Department's research efforts in the field, told the New York Times. "You don't have suppliers. You don't have a workforce. You don’t have equipment. You have to start from scratch."

China also has complex challenges to deal with in an effort to produce or maintain global leadership in the field. But if there is one thing that an arms race in the midst of a cold war guarantees, it is that each country will allocate all the necessary resources, financial, human and otherwise, to ensure it will win.