Analysis

Won’t work: Only WeWork asset left is investors’ bitter lessons

For years now, the co-workspace company has been operating in a problematic and dangerous business model that has made it the poster child for everything that is wrong in the technology sector

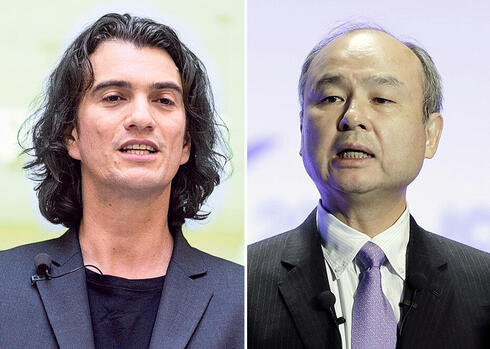

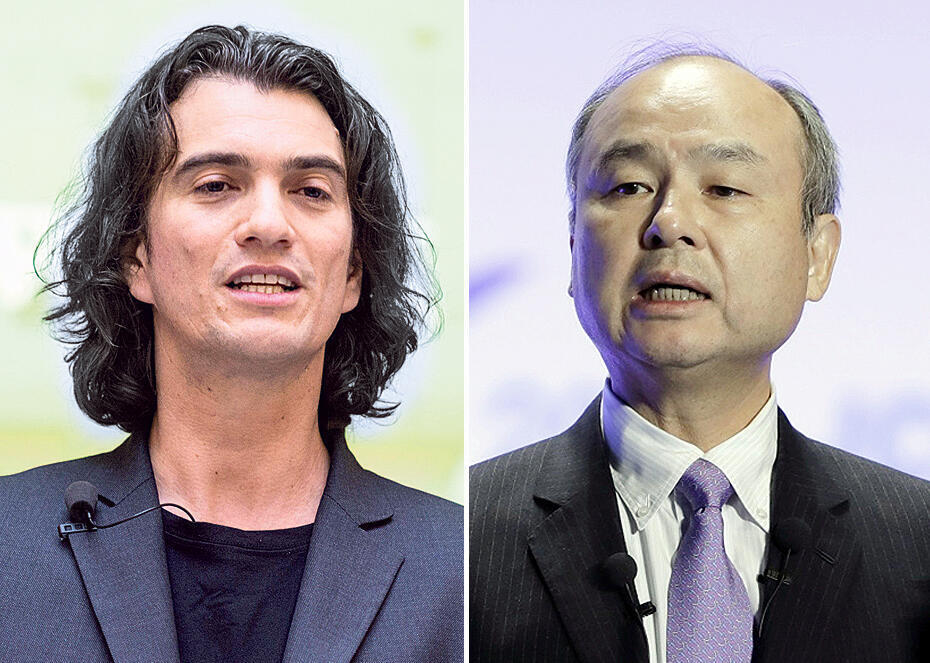

With a four-year lag, WeWork reported on Wednesday that it doubted its ability to survive as a functioning business. The co-working space company founded by the ousted founder and CEO Adam Neumann, published the dire warning in its second quarter report alongside a a loss of $696 million in the first half of the year. In total, in the last three years, it recorded cumulative losses of $10.7 billion. WeWork said that if its situation does not improve, it will have to consider options such as selling assets, reducing business activity and even filing for bankruptcy.

WeWork suggested a multifaceted approach in its reports: renegotiating lease terms for their operated buildings, tackling subscriber abandonment, constraining capital expenditures, and exploring the possibility of issuing securities. In simpler terms, they aim to reduce costs, boost revenues, and attract investors.

Unfortunately for WeWork, which raised capital at a valuation of $47 billion in January 2019, their current financial predicament cannot be adequately attributed solely to macroeconomic conditions and market oversupply. Over the years, the company has operated under a problematic and precarious business model that epitomizes the darker aspects of the technology sector. One ongoing risk for the company has been the failure to attract a sufficient number of subscribers to renew short-term agreements at rates high enough to cover their rent obligations for long-term contracts. Their operations remain susceptible to competition due to a lack of innovation, and with costs differing across regions.

In light of these challenges, the company has amassed cumulative losses of at least $16 billion over its 13-year existence, burning $22 billion of investor funding (including debt). The company ousted its founder, Adam Neumann, and saw an exodus of senior executives who aimed to stabilize its operations. Unfortunately, the manner in which the company conducted itself significantly tarnished the global brand it had built, to the extent that WeWork's representatives in Israel sought to distance themselves from the global brand.

Related articles:

The saga surrounding WeWork has spanned years. A non-fiction book on the topic has already been published, becoming a bestseller, while a documentary film and a series have been produced. Regrettably, this saga is not unique to WeWork; rather, it reflects a broader phenomenon. Numerous startups, funded at an astonishing pace by venture capital investors, have adopted a strategy not aimed at disrupting outdated systems but at distorting markets and stifling competition. WeWork, with backing from venture capital, established workspaces near competitors' locations, offering rental prices competitors couldn't match. They often extended a "transition bonus" to entice customers to terminate existing leases, maintaining these prices until competitors folded.

In a study by lawyers Matthew Wansley and Samuel Weinstein, this method is labeled "venture predation." It unfolds in three stages: first, venture capital is infused to create market-disrupting tools; second, the startup undercuts competitors' prices to eliminate them from the market; and third, once the startup attains a dominant market share, investors (and sometimes the founder) sell shares to those anticipating profit. The private nature of these companies obscures their cost structure, fostering the perception of market dominance through fair competition. This trend has produced substantial loss-making companies such as WeWork, Uber, and Lyft, but it has also yielded profitable investments. Benchmark, for instance, invested $12.5 million in WeWork in 2012, later selling its stake in 2017 and 2019 for $315 million.

Neumann himself profited over a billion dollars from share sales and a departure settlement. "While subsidizing our lifestyle was enjoyable," Wansley and Weinstein write, "predatory behavior carries tangible societal costs. If an enterprise can hike prices beyond competitive levels, it directly harms consumers paying these inflated prices."