Blood, ashes, and heroes: Inside the gut-wrenching reality of Israel's darkest day

The two-month long process to recover and identify the bodies of Hamas’ victims on October 7 has involved a multi-pronged national effort that includes volunteers from ZAKA, archaeologists and forensic analysts who have spent their days doing this, at times, dangerous, exhausting, sometimes tedious, and always painful but essential work. CTech spoke with three volunteers about their experiences over the last two months.

“I remember seeing bodies strewn throughout the streets, before we even got into the kibbutzes. There were cars lining both sides of the roads riddled with bullets and burned to the ground. Once we got into the kibbutzes, it was like entering a scene from a horror movie.”

- Josh Wander, ZAKA International Spokesperson

“It can take days working in one specific home just to clear the major rubble and get to the human remains. These homes were completely burned down, the furniture burned to a crisp. We go into a home that’s been burned and all you can recognize is ash. You don’t even know where to start.”

- Dr. Joe Uziel, Archaeologist

“When you extract DNA from these samples it is usually degraded and you have no idea what the actual quantity or quality of the DNA will be. Because so many places were burned, you have to deal with burned samples, which is another factor in the degradation of the DNA.”

- Prof. Gila Kahila Bar-Gal, Forensic DNA Analyst

* * *

In the wake of Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7th that left 1,200 dead, 240 hostages, and many unaccounted for, a large and multifaceted effort was launched to recover and identify the missing and murdered. The coordinated response has involved volunteer organizations like Zaka, the military, the Rabbinate, police, and forensic analysts, each playing a crucial role in addressing the aftermath of the horrific event. The massacre, unprecedented in its scope and brutality in Israeli history, has also made the recovery and identification process of victims uniquely challenging.

Typical procedures and protocols proved inefficient to address the magnitude of the disaster. With countless bodies reduced to ashes and unclear intelligence regarding those abducted to Gaza, numerous Israeli citizens – from children to grandparents – were declared missing. Authorities have been engaged in the near insurmountable task of identifying the dead and granting clarity, if not comfort, to their loved ones.

CTech heard firsthand accounts from three volunteers engaged in the harrowing process of identifying the victims of October 7th: Josh Wander, a volunteer and international spokesperson for ZAKA who recovered bodies from the sites of the massacre; Dr. Joe Uziel, an archaeologist recruited to search for human remains at the murder sites; and Prof. Gila Kahila Bar-Gal, who is engaged in DNA extraction when no other means of identification is possible at the Abu Kabir Forensic Lab.

Related articles:

Part I: Recovering the dead

“I remember seeing bodies strewn throughout the streets, before we even got into the kibbutzes. There were cars lining both sides of the roads riddled with bullets and burned to the ground. When we entered the kibbutzes, it was like walking into a scene from a horror movie,” says Josh Wander, the international spokesperson for the ZAKA search and rescue organization. In the last two months, the PR manager and married father of six has spent his days alongside thousands of other ZAKA volunteers recovering bodies of victims from the sites of the October 7th massacres.

Wander says that the recovery efforts were extraordinarily difficult both physically and emotionally. “We attempted to the best of our ability to document the bodies we were collecting. We would bring a body out of the house, document which house it came from and which part of the house, and try to identify it when we could.

“I was in Be’eri, Alumim, Kfar Azza, and Reim in the first few days. It was still an active conflict zone and we were surrounded by combat soldiers to protect us during our recovery of the victims,” says Wander. “Some volunteers were actively recovering victims when a firefight broke out with terrorists. A soldier was killed and volunteers had to recover his body as well.” Wander says that his team was forced to leave many times due to infiltration or suspected infiltration of terrorists, while recovering bodies under near constant rocket fire.

Wander is one of thousands of mainly ultra-Orthodox volunteers with ZAKA. He has volunteered with the organization for over ten years, where he’s been on the frontlines of the most grisly scenes. “We deal with any death due to unnatural means - car accidents, terror attacks, suicides - we’ve seen them all; nothing compares to the scale and horror of what we saw on October 7th.”

ZAKA was established over thirty years ago following the wave of bus bombings and suicide attacks during the Second Intifada. The organization focuses mainly on recovering and moving bodies and then transporting them to, in this case, the Shura military base which has been turned into a morgue. ZAKA volunteers work under the Israeli Police and are considered to be police volunteers. They typically focus on recovering the bodies of civilians, working alongside an army unit responsible for recovering bodies of soldiers and other state personnel including police.

After spending the first several weeks of the war volunteering with ZAKA, Wander was relocated to Shura as an army reservist. “My real job in the army is in the National Emergency Management Authority. Shura was created for that purpose - the possibility of a major national disaster like an earthquake, in which case there could be thousands of dead to identify, but nobody ever thought that it would be used for this.”

Identification of the bodies mainly took place at Shura. “We began with fingerprinting when possible; it's somewhat easier in Israel because we have a biometric database due to the army. But many victims were not able to be fingerprinted because they were children or because their bodies were so mutilated. In such cases other methods were used like DNA.”

Wander says that the scale and nature of the massacre has been extremely traumatizing for all volunteers, including for even “the most seasoned veterans who deal with the most horrific scenes on a regular basis.” There was a “non-stop flow” of army psychologists at Shura to treat volunteers and other people working there. “I found out later that the army psychologists have their own psychologists because they received secondary trauma from speaking to us and needed therapy of their own,” says Wander.

In the two months since 7/10, most of the bodies from the sites of the massacre have been removed by ZAKA and the army. Bodies that have not yet been identified are at Shura or at the Abu Kabir Forensic Lab to determine their identities via DNA analysis.

Wander says that ZAKA's latest mission is to go through hundreds of vehicles belonging to victims who tried to flee from places like the Nova Music Festival. “Some were burned to the ground and we’re going through them to see if there are any remains, even blood stains.”

Testimony from ZAKA volunteers has become critical as Israeli authorities seek to collect evidence of Hamas’ crimes and amidst rampant disinformation that denies or minimizes them. However, while Wander says that testimony is important, he also is concerned that respect and dignity of the victims be protected, that lines ought to be drawn on the dissemination of images of the bodies.

“The Holocaust happened 80 years ago and there are very few survivors living today. There was no social media and the Nazis tried to cover up what they did. But what we are seeing now happened just a few weeks ago, there is a plethora of information, testimony from first responders and victims, plenty of videos and images,” Wander says. “If someone is still willing to deny what happened, then there is no amount of evidence that can convince them otherwise. They’ll come up with some kind of conspiracy theory to justify their narrative.”

ZAKA has only seven paid staff members, and relies on thousands of volunteers, which Wander says isn’t only for budgetary reasons. “People cannot be paid for the work that we do. You have to feel very strongly to do it. Volunteers risk their lives daily to do it and we do so because we believe that we’re doing God’s work.”

Part II: Searching for evidence

After ZAKA and the army completed the initial step of recovering and identifying bodies when possible, the bodies were transferred to Shura medical base to be processed. However, in many cases, there were no bodies to recover. In such cases, the first requirement is to identify any remains. This is a challenge due to the fact that Hamas burned down houses, cars and other places where victims hid, in an attempt to coax them out or to burn them alive. Many homes in kibbutzes such as Be’eri and Kfar Aza were burned to the ground, and ashes are all that remain.

That’s where archaeologist Dr. Joe Uziel and his team come in. Uziel is the head of the Dead Sea Scrolls Unit at the Israel Antiquities Authority, a special unit dedicated to conservation, documentation and research surrounding the Dead Sea Scrolls - perhaps Israel’s most important archaeological find. But for the last two months, much of Uziel’s work has been devoted to sifting through ash and rubble at the sites of the October 7 massacres, searching for human remains.

“We are applying the methodology that we’re trained with to this modern, immediate, horrible event to provide information that maybe other teams couldn’t,” says Uziel. “We’re primarily going into these contexts, shifting through the ash, removing rubble, searching for personal adornments, things specific to an individual, tooth crowns, but mostly bones; anything that can then be used to identify missing people.”

Uziel says that they have collected the remains of over one hundred individuals and have made over ten positive identifications that were initially listed as missing. “While that’s horrible news," he says, "I still think that it’s important for the families and communities to have that closure and know what happened to their loved ones.”

The project began about two weeks after October 7, when the army approached the head of the IAA who quickly established a team of expert archaeologists to support the efforts to identify victims. No one really knew how significant the results would be, Uziel says. “We’re used to excavating in contexts that are hundreds, and more often, thousands of years old. But the training that we have is to identify the most minute evidence within a specific context, and at the end of the day, our ability to identify the materials properly gives us that ability to work through the masses of destruction.”

The project now consists of roughly thirty archaeologists who work in rotation about two to three times per week alongside army personnel. The process is laborious, demanding enormous concentration and time, requiring archaeologists to literally pore over every grain of sand or debris that they come across. “I can’t estimate how long it will take. It can take days working in one specific home just to clear the major rubble and get to the human remains. These homes were completely burned down, the furniture burned to a crisp. We go into a home that’s been burned and all you can recognize is ash. You don’t even know where to start.”

The damage is so great in these cases that the existing remains are mainly limited to bone fragments - as complete bones are also extremely rare - which is not simple to identify amidst ash and debris. Uziel likens the search for these remains to “looking for a needle in a haystack.”

After Uziel’s team has identified bone fragments, they then send the specimen to Shura medical base where they perform the DNA analysis in their labs. But Uziel notes that often these types of human remains are much more difficult to identify because they have been burned so badly making them “much more fragmentary and very small.”

Uziel says that they are using the exact same methods as they would in a typical archaeological context. “I excavate sites in Jerusalem that are 2000-years-old and we use the same tools. We work with a brush, a trowel, a hoe and, if we’re working through heavier rubble, we work with sieves.” Having said that, Uziel says that he had no idea that archaeological methods could be used in a modern context. He’s since learned about cases where archaeologists are used in police work, but nowhere else have they been utilized at this scale or in such an extreme context.

“I never expected to be doing this - to be looking at a nightmare. On the other hand, I feel like this is the most important thing that I've done in my professional life," he says.

Uziel and his team have been to most, if not all, of the sites of the October 7th massacres, and the physically and emotionally taxing work of sifting through the final remains of those who were brutally murdered is impossible to ignore. “The main challenge is being able to separate yourself from this as much as possible, which isn’t easy considering that some of us know people who were impacted directly,” says Uziel. “We’re also very focused on the work itself, and once we’re immersed in the technical process, we make a switch to ensure that we’re doing our job the best way that we can.

“On the one hand we’re seeing very difficult things, but at the end of the day to be able to say that our team brought some contribution to moving forward and to healing is empowering, so you gain strength from that.”

Part III: Extracting the DNA

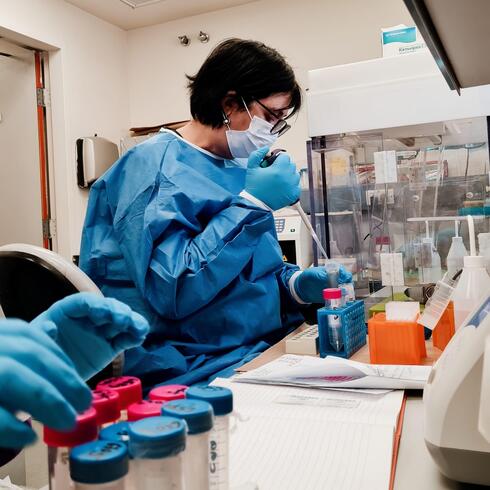

Like nearly every Israeli, after October 7th, Professor Gila Kahila Bar-Gal immediately began searching for ways to volunteer. “At first, I volunteered in my moshav as much as I could: making meals for soldiers, collecting items for families, but I wanted to use my knowledge,” she says. Kahila Bar-Gal is an expert in ancient DNA and wildlife forensic DNA analysis at the Faculty of Agriculture, Food, and Environment at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Before the war, her research was focused on historical and prehistoric non-human DNA. After October 7th, she was recruited as a volunteer to the Molecular Forensic Laboratory led by Dr. Nurit Bublil at the National Institute of Forensic Medicine known as Abu-Kabir.

Kahila Bar-Gal brought her team with her, including technician Dr. Galit Eakteiman, PH.D student Ksenia Juravel, and Yulia Abramov, Scientific Director of the bio-anthropological collection at the National Nature History Collections at Hebrew University. “I have other students who would have also come but they are in reserves,” she says.

For the first month following October 7th, Kahila Bar-Gal says that she was doing this work full-time. Now she only works at Abu Kabir 3-4 times a week, and only recently started going back to her regular job 1-2 times a week. Her team focuses on DNA extraction - the first step in a forensic process that is followed by amplification of the DNA, culminating in the analysis of the results which is conducted by lab researchers. “In a sense, extraction is the most critical stage because nothing else can occur without it,” she says.

The team has to determine where to isolate and extract DNA from, and physically drill into bone or tooth samples to do so. “Once we have the DNA, they quantify it in the second stage and amplify it. No data is released until the analysis team is confident that they have a full profile that they can rely on and that it hasn’t been contaminated.” She says this is the same process no matter the age of the sample. “When you’re talking about archeological samples, they could be 50-years-old or 15,000-years-old, and in both cases, once the organism has died, the same chemical processes destroy the DNA.”

However, because so many victims were found in homes, cars and other sites that were burned, the amount of salvageable DNA is sometimes so miniscule or the quality so degraded that getting a DNA sample is extremely difficult. “When you extract DNA from these samples, it is usually degraded and you have no idea what the actual quantity or quality of the DNA will be. Because so many places were burned, you have to deal with burned samples, which is another factor in the degradation of the DNA,” she says.

While many victims were able to be identified early on, there are far too many who couldn’t be, meaning that DNA analysis is the only option, which is a lengthy process under normal circumstances. “It takes time to get DNA analysis - typically 2-3 days. We are limited with the number of samples that we can process because we’re trying to avoid contamination between samples. People are working around the clock to get answers.”

Kahila Bar-Gal says that she tries to just focus on the work, but that in a country this interconnected and a disaster this widely felt, it is impossible not to feel the emotional toll. “I was happy that the only thing that I saw were numbers and data and not names,” she says. But the impact on her team was felt. “It was hard for them. Sometimes I would tell them not to come in and take the day off.”

However, much worse than analyzing the DNA of victims of the massacre, including people that Kahila Bar-Gal may have known, was attending a conference in Europe to discuss her experience, where she was confronted with denial of or justifications for Hamas’ crimes.

“It was much harder dealing with those attitudes, with people not knowing all of the facts or ignoring the massacre that happened, or saying that Israel brought it upon itself,” says Kahila Bar-Gal. “The ignorance of people talking about things when they don’t know the evidence made me angrier than what they actually thought. If you want to have a conversation about this, then you should know the facts. That was much harder than all of the work that I did in the last two months.”