"An agreement with the Palestinians is inevitable because they will acquire nuclear weapons"

Prof. Joel Mokyr paints a nightmare scenario where both Israelis and Palestinians, and many others, have nuclear capabilities. But he also thinks that this is what will lead Israel to an agreement with the Palestinians

"Right now, I am not optimistic: both sides do not think that any compromise or arrangement is possible. Everyone that I speak to, and these prophecies tend to fulfill themselves when everyone is pessimistic, believes that this will be the result. It's like an economic crisis - if everyone thinks there will be an economic crisis, then there will be one," says Professor Joel Mokyr.

Mokyr is among the most prominent and well-known economic historians in the world. He grew up and studied in Israel, and in the 1970s began building an acclaimed international career. Among other things, he edited the Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and has been a professor at Northwestern University for many years. So, when he talks about self-fulfilling pessimism, he knows it well from history: Mokyr examines how worldviews influence technological advancement, for example, how the belief that they are wiser than those before them, led new generations to technological advancement in the 16th-18th centuries.

There are long-standing blood feuds that no one thought would ever be resolved, and they were.

"There are encouraging examples here and there. We've seen that even people who hate each other can sit down and reach an agreement from time to time. A classic example for me will always be Northern Ireland, a centuries-old conflict and hatred, and look at it today. I was in Belfast recently; they don't like each other, there's mistrust and suspicion, but they don't shoot each other. Even in Yugoslavia, there was a bloody war, and one day they reached an agreement. Today it's not paradise; they're not sitting around the campfire holding hands, but they're not shooting each other. And as long as they're not shooting, I'm happy.

"And there's a bigger example - the Germans and the French. For hundreds of years, there was a mutual hatred between them; Napoleon wreaked havoc in the German states, and then came the Franco-Prussian War and the World Wars. In 1945, the French deeply hated the Germans, and rightly so, and today years have passed, and there's no animosity - the French drive Volkswagens."

Related articles:

The question is whether this is possible in the Middle East.

"There is some hope. At the moment no one sees it, but it can change, and in the end, logic, reason, and goodwill may prevail over the aggressive urge to defeat the other side. After October 7th, there was a feeling that we had to defeat them, eliminate them forever. This vengeful urge is destructive, and it exists on both sides, but it's an urge that human culture needs to learn to overcome because, if not, the end will be bitter. I'm old enough to remember how much we hated the Egyptians. They were our sworn enemies, and in the end we made peace with them."

But you've spoken about how there is so much pessimism, so how are you still optimistic? Maybe we won't succeed in reaching an agreement?

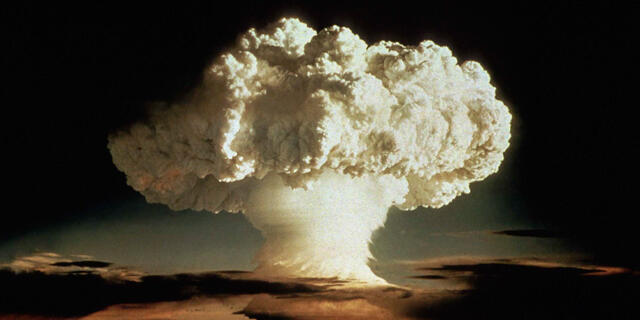

"Over time, it will be inevitable because the other side will acquire nuclear weapons. Palestinian resistance movements will somehow acquire such weapons and threaten to drop a bomb on Tel Aviv, even a small bomb. A suicide bomber doesn't care if he takes ten people with him or a million. With time - much beyond my lifetime - we must reach an arrangement or there will be mutual destruction and annihilation, because nuclear weapons will also kill Palestinians."

‘Anyone who thinks the Palestinians won’t acquire nuclear capability isn't paying attention’

Mokyr's unique perspective, combining economics, policy, security, and politics into a broad historical picture, allows him to analyze our current situation from a bird's-eye view. From there, he returns to what he knows particularly well: the connection between technology, progress, destruction, and growth. "Continuing to live as we have in the past 75 years is not a long-term equilibrium - technological improvements upset the balance, and nuclear weapons are just one example of such technology," he says. "For many years we thought we could drop the Palestinian issue from the agenda, but October 7th proved that impossible, and still people don't think enough about it in the long term. In the long run there is no alternative but an agreement. Not because of justice or fairness - these things are irrelevant. What's important is that both sides can destroy each other, and that's the end of the story."

For many, the issue of Palestinians gaining nuclear weapons feels far-fetched.

"I am very, very concerned about it, and those who are not worried, those who think it won't happen, aren't paying attention to what's happening in the world. The spread of nuclear weapons is inevitable. I know people in Israel have been talking for years about what will happen with Iran's nuclear program, but Iran is just one example. There is a very large, very hostile, and very destabilized Muslim country with nuclear weapons - Pakistan. The weapons are not currently directed against us, but no one knows what will happen in the future. If Iran has nuclear weapons (and, in the long run, I think it's inevitable, no matter how much Bibi and others object), Saudi Arabia will also have them, and from there, it will spread further. It's just a matter of time before terrorist organizations get a hold of them."

Conversely, there have been ongoing discussions about Israel's nuclear weapons for years.

"It’s a deterrent to know that one cannot push Israel too far into a corner. Look, the United States and Russia have been facing each other with nuclear weapons for over 75 years, and since Nagasaki there hasn't been a nuclear attack. But it's like the person who falls from the 95th floor and at the 8th floor he says, 'So far, everything is okay.'"

As an economist who always emphasizes the importance of growth from technological changes, now you're talking about the threat of technological changes.

"Our ability to develop means of warfare and means of destruction advanced hand in hand with other technological advancements, and now we have technologies that pose an existential threat to the world, means of destruction that can wipe out life on Earth. This possibility seemed absurd in the Middle Ages and early 20th century, but today it is a real threat. In just a few hours, we could eliminate all technological advancements and improvements to our quality of life. It's a chilling nightmare."

And this nightmare is what can lead us to a peace agreement?

"Yes. As mentioned, we've seen longstanding animosities resolved. However, it requires goodwill, time, and external encouragement. The United States played a crucial role in resolving conflicts in Ireland and Europe."

‘There are no good wars, and politicians are a market failure’

It's not easy to hear what Mokyr has to say, because what he has to say is difficult, but also because of who he is. Mokyr has always been known as an optimist, someone focused on human growth, who regarded technology as an inexhaustible source of growth (unlike, for example, international trade and human capital, which are limited sources of growth). When other researchers claimed that technological changes reached their peak, Mokyr disagreed. But now it seems that he has fallen into a deep crisis regarding what he believed in for years, more precisely, what he presented for years based on comprehensive research and deep thinking. It wasn't a belief - these were the facts. And now what?

"The problem is that technological progress was not accompanied by institutional progress. We failed to learn how to avoid wars," he explains. "It seemed that we were moving in that direction; during the period between Napoleon and World War I there were 100 years of relative peace or relatively short wars. But the 20th century showed that things were not that simple. Even after the end of the Cold War, there were people who thought that was it, that this was ‘the end of history,' and since then we've learned again that human nature allows characters like Vladimir Putin to rise, who think it is worth it to destroy world peace and start new wars. It's clearly something that humanity can’t entirely get rid of, this kind of Putinism."

It’s often said that the total number of casualties in wars has steadily decreased over time.

"Prof. Steven Pinker is focused on this area, on the decline of violence, but it is based on a certain statistical illusion - he looks at the mortality rate of the total population. The issue is that there has been huge population growth over time, and simultaneously, the absolute number of deaths has increased. So it's a question of what to look at - the number or the ratio. And I'm not just looking at wars like those in Gaza and Ukraine, but also civil wars, like in Sudan, for example, where there are already 14 million refugees. Pointless violence that kills people and destroys lives still exists."

Population growth is a result of technological improvements, and some technological leaps come as a result of wars.

"You can't use technological influences to justify war - these benefits are secondary. Wars certainly accelerate technological processes, governments and private companies engage in high-level research and development. For example, in 1914 there were about 500 airplanes worldwide, but by the end of the war there were 100,000, and they were much better. But this would have happened without the war, just more slowly. The two main technological processes that shaped the economic reality in the 20th century were nuclear technology and antibiotics, and both happened without war."

Regarding creativity, there's a classic quote from the film The Third Man: "In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love - they had five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock."

"I've heard this story hundreds of times and, forgive me, it's just nonsense. It's true that there are countries where even during warfare, they managed to create culture. But generally, war destroys culture, destroys cities, destroys talented people. The Italian Renaissance happened despite war - not because of it. And not all wars are the same; those in Italy, for example, did less damage to the civilian population. They were wars of mercenaries and generally took place outside the city, so their damage was limited.

"When you have a serious war on a large scale, it's a different story. In the Thirty Years' War in Europe in the 17th century, the damage to the German people and culture was enormous - one third of the population was killed or left, and many cities were destroyed. Germany needed about 100 years to recover. And in France, Louis XIV led countless wars, and when he died in 1715, he left a devastated country, with famine, suffering, and a terrible plague. It took them decades to recover. You can also look at post-World War II Germany or Japan. So don't tell me that in some way war brings good - war is by definition designed for destruction and killing. You don't need to have a doctorate to understand that it generates costs and not produce."

In the Israeli context, we often connect the constant security threat to the ongoing pressure for the high-tech industry to flourish, especially in cybersecurity.

"And, if it wasn’t for the security crises, Israel's growth would have been even faster. It's hard for me to believe that Israeli ingenuity wouldn't have thrived without security pressure; Israel has all the potential to thrive thanks to human capital, culture, and creativity. When you look at data, you see all the time that wars destroy capital and jobs. Wars kill people in their working years; people who die at the age of 21 instead of living until 70, leaving widows and orphans. As an economist, I am ultimately interested in utility, quality of life, and social welfare, and war, by definition, reduces utility."

So war doesn’t contribute to technological advancement, or creativity, but what about the formation of national identity and political consolidation?

"I particularly disagree with this claim because, in the short term, war indeed has a high cost, but in the long run, it brings about political consolidation and a common goal. Wars do create national unity - this is how Bismarck united Germany in the 19th century. But I don't feel that it’s a tremendous improvement for humanity to have a state called Germany. As an economist, I don't see why it is so wonderful, except that Germany became very aggressive and triggered World War I and then World War II.

"There is a famous quote by sociologist and historian Charles Tilly: 'War made the state, and the state made war,' but as an economist, I ask: does having large and powerful states improve economic welfare? There are small countries in Europe that didn’t unify, like Luxembourg, and the standard of living there is higher than any other country in Europe. War is not necessary to create economic well-being and quality of life, which are the main goals of the economy. I agree with Benjamin Franklin, who said: 'There never was a good war, or a bad peace.’

And yet, we are in Israel. How is this relevant to us?

"Israel has many unique characteristics. It is a case like no other, there is no example like Israel’s in all of history, so what we can learn from other countries is limited. The claim that if not for Israel’s security pressure Israeli innovation wouldn't have existed, maybe there's something in it, but I'm very skeptical."

Regarding the notion that there are no good wars, at the beginning of the 20th century, Norman Angell published "The Great Illusion," a study in which he argued that there is no chance of a war breaking out in Europe because no country has an economic interest in it, and they would all just lose.

"It's true, and it's a good question: why are there wars if they are so destructive and irrational? There is one approach that connects it to the famous prisoner's dilemma; each side thinks the other wants to defeat them, so they choose the less optimal strategy, creating a balance where both sides lose. Another approach, from the world of political economics, poses a question: those deciding on war do not pay its price. They sit in the capital, not on the battlefield, and even if war has a very high cost for the economy and society, from their perspective, it might be worthwhile. This is what we call the ‘principal-agent problem,' where an agent or representative holds different interests from those they represent. For an officer or politician, it might be an opportunity to rise in rank, seize power, or gain publicity."

And when the war ends, how do you recover?

"In the 20th century, countries needed 10-15 years to recover. Every war requires a transfer of resources from civil society to the military. You need to recruit manpower, equipment, products, and you need to fund all of this. Usually, you can't raise taxes during wartime, so almost every war leads to a rapid increase in national debt and after the war, they pay for it. In Germany, there was hyperinflation that caused immense social and economic destruction after World War I, enabling the rise of Nazism. In Britain the economy was very weak in the decades between the World Wars. Many countries needed fifteen years of rationing after World War II. That's how you recover from wars."

‘What we are seeing in the United States is not antisemitism’

In Mokyr’s analysis of the current war he acknowledges tensions in the United States, where he lives and has also experienced the change in attitude towards Israel. "There are debates, arguments, and protests on campuses," he says. "But let's not exaggerate. I came to the United States during the Vietnam War, and it was much worse then, people were shot on campuses."

But there wasn't antisemitism back then.

"I've been in the United States for 50 years and have never encountered any antisemitism. It's true that I don't move in circles that represent the whole country; I live in the academic world, and in my two departments, history and economics, there are quite a few Jews. But I've never come across any expression of antisemitism, anyone saying 'this Jew' or something like that.

"And one must distinguish between antisemitism per se and people who oppose Israel’s behavior. For many people, they have nothing against Jews - some of them are Jews themselves and stand and say 'Free Palestine.' Is someone who shouts 'Free Palestine' antisemitic? It's hard to say. They are anti-Israel, maybe anti-Zionist, but there are many nuances. Some oppose the very existence of the State of Israel because Jews shouldn't have a state, and there are those who think there should be a state, but they oppose settlements and creeping annexation. There are also Israelis like that. And these distinctions are critical.

"Antisemitism in the 20th century was a movement of fascists, of right-wing people who hate Jews unrelated to Israel - and its classical anti-Semitism, like neo-Nazis today. These people are entirely different from those shouting 'from the river to the sea' on campuses, who oppose Israel and its actions, and it's true they sometimes lack nuance in trying to understand the reasons behind Israel's behavior."

Is opposition to Israel's activities not a renewed form of the same classical antisemitism?

"No, I don't buy that, not in any way. I would even say the opposite: in the first decades after the establishment of the state, public opinion worldwide was pro-Israel - look at the era of Ben-Gurion and the Six-Day War. Only after 1967 did sympathy wane, and it began to reverse. So to say that what we see now is a reincarnation of classical antisemitism in Europe is simply unfounded. Antisemitism has always been a phenomenon of the extreme right. Even in France during the Dreyfus Affair, there was no left-wing antisemitism in Europe. It's true that the European left and the American left strongly distance themselves from Israel's policy, but to say that this distancing is antisemitic and unrelated to Israel's actions is wrong."

So how did we arrive at hearings with university presidents unable to condemn attacks on Jews?

"No one suspects them of being antisemitic. They are between a rock and a hard place: a significant portion of their students and some faculty members are pro-Palestinian, and on the other hand, there are pro-Israel donors. So they try not to alienate either side, and in doing so, they annoy both. I don't envy them; I wouldn't want to be the president of an American university today."

So it's not antisemitism but criticism towards Israel - does that matter to Jews or Israelis?

"Maybe not. The criticism should worry Israel; it's losing its allies. The American left always supported Israel, and in recent years, it has flipped, and those supporting Israel are precisely right-wing and evangelical groups and Donald Trump supporters, and that's not great in my opinion. Israel has always been a kind of island of democracy, enlightenment, and liberalism in the world, and today that image is eroding. I’m not sure if it's a price we can afford when we are a small and open economy dependent on trade and connections with the world."