Opinion

Astronauts May Not be the Only Thing Lost in Private Space

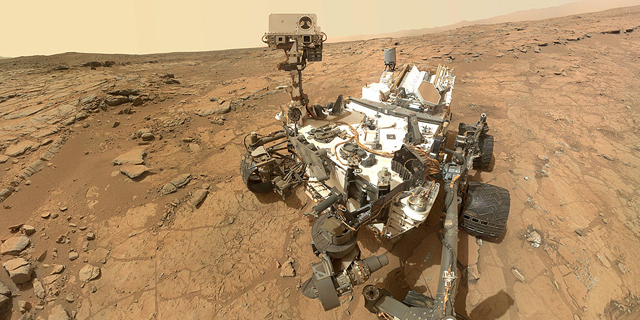

Astronauts have been absent from space exploration for some time. To wit: Mars is the only planet in our solar system that is known to be solely inhabited by robots

Dov Greenbaum | 15:02, 06.12.18

Does our general apathy regarding the safe touchdown of the Mars Insight robot last week, imply that space exploration no longer excites and exhilarates us? Perhaps it’s because, in contrast to the Space Race of decades past, our current efforts are conspicuously missing what was one of the most alluring elements of space exploration: brave and heroic astronauts.

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

Astronauts have been absent from space exploration for some time. To wit: Mars is the only planet in our solar system that is known to be solely inhabited by robots. With three of the 15 robot missions to Mars still operational, robots seem to be the preferred method of the vast majority of new space-based efforts. Robots are cheaper to operate in space than humans, they work 24/7 and they don’t need concomitant life support systems, food, water, or shelter. Also, whereas the potential for loss of human life in space exploration has always been a check, if not an actual impediment in space exploration, the same cannot be said about the potential loss of a robot. No matter the dollar cost, its just money. There is at least one group bucking this trend: Elon Musk’s SpaceX which aims to put people on Mars via cost-efficient reusable rockets. Elon Musk himself now suggests that there is a 70% chance that he will eventually move to Mars. Several times he had said on video he would like to die on Mars, just not on impact. Putting real people far beyond the low-Earth orbit of the International Space Station—for the long term on the Moon, Mars, or other celestial bodies—raises a number of real and relevant social, ethical and legal concerns. Most immediate perhaps, are issues relating to land ownership. Who will own the future habitats on Mars? History has repeatedly demonstrated that cheap homesteads are a strong incentive for developing remote settlements. But things are rarely that simple in space. Academically, the current understanding of the various relevant international treaties suggests that, at the minimum, any ownership claim to any part of any celestial body is at least legally questionable. But facts on the ground suggest otherwise: a recent Sotheby’s auction of moon samples implies that ownership is legally possible and could be internationally recognized; you can’t sell something you don’t own. But while we remain a number of years away from realizing Musk’s Mars ambitions, there are other SpaceX plans that should be equally alarming. This past spring, SpaceX received permission to launch a constellation of satellites that would dwarf the entire population of all satellites that have ever been launched. In contrast to the hefty devices that make up much of the current satellite numbers, SpaceX’s fleet would be comprised of tiny microsatellites. SpaceX is not the only one tossing hundreds of microsatellites into orbit, in fact, for the cost of a luxury car, even you could conceivably send your own satellite into orbit. While microsatellites or cube-sats (10x10x10 cm) are cheap and easy to deploy, they have a failure rate, that in the past has approached 50%. Satellite failures are non-trivial. Best case, they become space junk that quickly finds itself in a decaying orbit and eventually harmlessly burns up in reentry. Worst case, they transform into uncontrollable hypersonic projectiles, capable of incredible damage to other satellites and to space traffic in general. This latter eventuality has a name: The Kessler effect is a proposed model where a sufficient density of out of control orbital debris can result in a devastating cascading ping-pong effect of destructive orbital collisions. The solution to this problem is also non-trivial as the same aforementioned treaties fail to envisage the idea of space junk, liming the availability of easy legal solutions. And with the idea that one man’s trash may be another one’s treasure, it’s unclear how we might even go about the initial step of labeling what is and what is not space junk so that we can start dealing with it in a comprehensive and legal fashion. Consider, for example, that a nation or corporation might maintain a defunct satellite in its orbit simply to prevent others from appropriating a valuable flight path.

No Comments Add Comment