Opinion

The Holes in WeWork’s Colorful Prospectus

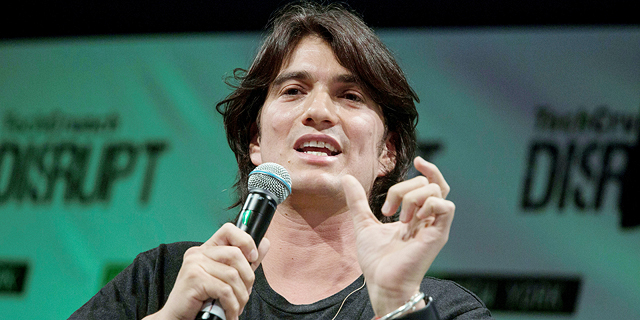

WeWork’s prospectus does not provide enough information for anyone looking to gain a deep understanding of the company’s business model. Will Adam Neumann’s charisma and vision be enough for investors?

WeWork—or the We Company, as it recently rebranded—published a prospectus that is more a philosophical-social manifesto with a cult of the leader undercurrent than it is a document that sheds light on the company’s business model, as a prospectus should do. It reveals WeWork’s approach to charity, compensation, environmental and social awareness, and meat consumption.

Potential investors who waited to receive an answer to the age-old question of what makes WeWork a tech company and not a real estate company were undoubtedly disappointed. Throughout its decade of existence, WeWork drew money like a tech company, raising its last $2 billion round in January according to a $47 billion valuation. The company has also reported a meteoric growth rate, one of the main characteristics of growth companies.

Throughout the years, WeWork has hinted that its business model is based on more than just leasing assets long-term and then renting them out short-term. The expectation was that the company had some sophisticated algorithms behind its contracts and pricing method, similar to Uber, which, though a transportation service provider, determines its prices using an algorithm.

If WeWork does have such an algorithm, it kept it out of its prospectus. The company’s filing reveals it has managed to balance its base asset expenses and its revenues only in the past year. Until 2018, it had spent more than it brought in, resulting in a loss of $3.6 billion over the past three and a half years. The company did not disclose its numbers prior to 2016.

In the past, there were hints that WeWork’s contracts were written to protect it in times of slowing growth or stagnation, but that was not discussed in the prospectus, either. Even the company’s disclosure regarding its new markets growth and development expenses—reminiscent of the research and development clause seen in the reports of tech companies—falls short. In fact, the prospectus does not provide enough information for anyone looking to gain a deep understanding of the company’s business model or prepare some kind of forecast.

What the prospectus does do is strengthen the understanding that WeWork is a real estate company with minimum future lease obligations of around $47 billion.

It fails to truly examine the stout competition that has sprung up since WeWork got its start, not just from traditional business real estate companies but from co-working companies such as LABS, Spaces, Techspace, and Impact Hub. Unlike the many dozens of times Adam Neumann’s name is mentioned—in reverent tones—in the prospectus, the words competition and competitors are only mentioned 21 times. Overall, the prospectus does not demonstrate WeWork’s competitive edge beyond stating its pioneer status and strong brand will enable the company to withstand competition.

Related stories

It could be said that the only thing that truly makes WeWork a tech company is its stock composition, intended—like in the case of Facebook and founding CEO Mark Zuckerberg—to ensure Neumann’s continued control over the company.

The prospectus, ironically enough considering WeWork’s new name, gives off the impression that it is about the I—Neumann—much more than it is about the We. The question now is, will Wall Street choose to trust Neumann’s charisma and vision over a deeper inspection of the prospectus’ small print?

No Comments Add Comment