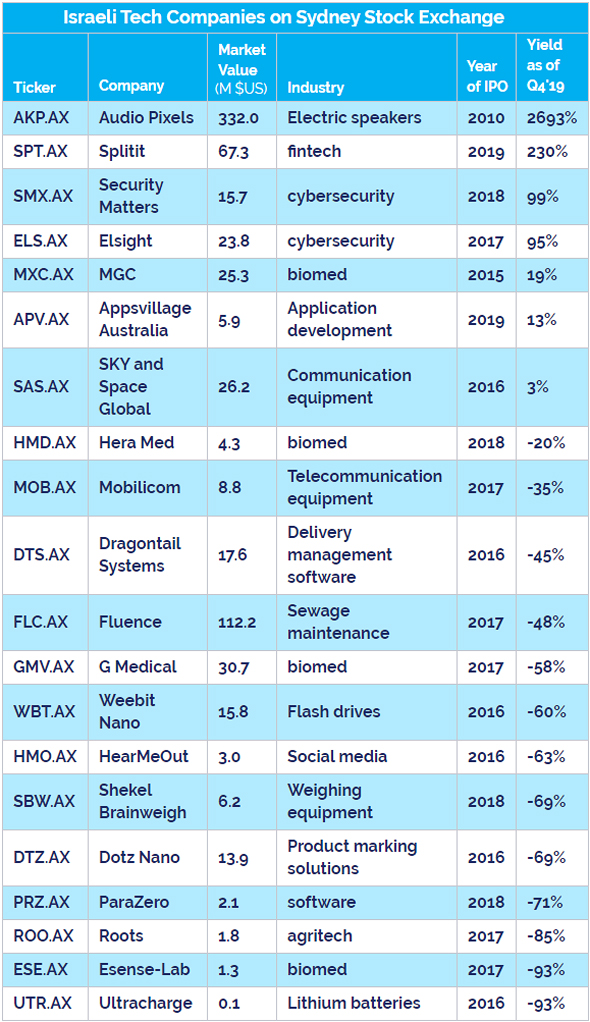

The Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), it would appear, is where Israeli companies go to die. To begin with, companies that are tempted to list on ASX are not likely candidates for a Nasdaq initial public offering or even a Tel Aviv one. But these companies’ stock performance on the Australian exchange creates an even more disturbing image. Out of 20 Israeli companies listed on ASX in recent years, during which the exchange was aggressively marketed in Israel, only seven are showing positive returns.

Calcalist examined the companies’ performance since their IPOs and up until late 2019, to neutralize any effect the coronavirus (Covid-19) crisis may have had. Even before the global pandemic shook stock exchanges around the world, most Israeli ASX-listed companies presented negative returns. About half of these companies are now traded at a market capitalization of around 50% from the one they had during their IPOs.

This being the case, most of the Israeli companies traded on ASX do not have market caps that justify them remaining public. Just two of these companies have market caps of over $100 million and one is valued at $50 million. The rest are somewhere behind, with market caps that are beneath their years, even for the private market. Together, these 20 companies were traded, as of late May, at just $714 million. Most of the Israeli companies listed on ASX are startups from different sectors, with a slight tendency towards biomedicine. Looking at their performance it is hard not to consider the possibility they only went for an IPO after they had trouble raising money from venture capital firms.

ASX has put a lot of effort into luring in Israeli tech companies. The most prominent investors in the exchange are Australian pension companies that invest their clients’ deposited funds. Since 1992, Australia’s mandatory pension law requires all citizens to deposit 9% of their pay each month, which has made Australia, with its 25 million residents, the third-largest pension market in the world, after the U.S. and Germany. A large portion of these pension funds, amounting to a total of nearly $3 trillion, is funneled into ASX, which is traded in and of itself at a market cap of some $10 billion.

Some 2,200 companies, 350 of them from outside of Australia, are currently traded on ASX, with Israel now the third-largest foreign supplier of companies to the exchange, after New Zealand and the U.S. Considering the low returns, however, it is unlikely that Australian pension savers are thanking Israeli companies for their involvement.

On top of seemingly accessible capital, what draws Israeli companies to ASX are its relatively lax regulation and filing requirements. These soft terms are also why the Israel Securities Authority (ISA) refuses to approve dual listing in Tel Aviv and Australia, despite ASX’s request, submitted some time ago. Estimates in Israel are that ASX is trying to pull a similar stunt to what the London Stock Exchange did when it established the Alternative Investment Market (AIM), which is aimed at companies with a low valuation and offers softer regulation.

After an initial flocking to AIM by Israeli companies with a profile similar to that of companies that turned to Australia, it became apparent that AIM’s loose regulation and low transparency come with a hefty price. A large number of companies that chose to list on AIM suffered a blow to their reputation as a result, which prevented them from later moving on to more central stock exchanges.

ASX’s filing requirements are indeed very convenient. Listed companies must file financial reports twice a year and the annual report required of them is significantly shorter than its Tel Aviv equivalent. Foreign companies listed on ASX are also required to add at least one local member to their board, but most opt for two Australian board members, at the advice of their underwriters.

Currently, all parties are mutually disappointed with Australian IPOs, according to one person familiar with the matter who spoke to Calcalist on condition of anonymity. “The Australians expected companies with sales that could achieve quick growth while the Israelis were promised higher valuations and are let down by their current market caps,” the person said.

Another person speaking on condition of anonymity told Calcalist that one of the companies now listed on ASX was considering listing in Tel Aviv, but the Australians gave it a higher valuation. When it came down to it, after the company already filed its prospectus in Australia, the underwriters cut its valuations and it ended up listing at a lower price then it would have in Tel Aviv, the person said. “If Tel Aviv was truly an option for tech companies, in terms of institutional investors’ interest, there would be no need to go to such a distant and expensive exchange,” they added.

Despite its predecessors’ disappointing performance, another Israeli company, Gefen Technologies Ltd., is getting ready for an IPO in Australia. The company, which develops digital marketing tools for insurance agents, intends to raise $15 million in Australia, after reaching $4 million in revenue in 2019 and presenting a $20 million revenue prediction for 2020. Unlike Gefen, Tel Aviv-based WAY2VAT Ltd. recently froze its plans for an ASX IPO.

In these post-coronavirus times of shrinking valuations, companies cannot be too picky but heading for an IPO at any cost could stain a company’s reputation for years.