As the Covid-19 vaccine arms race intensifies, big money is at risk

Governments want to be among the first to get their hands on the coveted solution, but they are also risking money that could be used to strengthen their healthcare system

The latest occurrences in the global vaccination market bring to mind what happened with food retailers shortly before a lockdown was announced. In March, Israeli consumers rushed to the supermarkets in a frenzy, lunging at canned food, toilet paper, and eggs, leaving behind empty shelves.

It will not be an overstatement to say that many governments are now on a similar hoarding spree with various pharmaceutical companies. The governments are after a very specific product, the necessity of which is non-debatable, but there is one small issue, it does not exist yet.

Even Though no company has yet proven it has developed a vaccine for coronavirus (Covid-19), the discourse around it is fueled by world leaders, especially U.S. President Donald Trump who somehow managed to convince everyone that a vaccine is just around the corner. According to Trump, who is leading the check signing campaign for the non-existent product, the vaccine is expected to hit the market shortly before the U.S. general election in November.

Now that everyone is convinced the whole process will be done within several months, the conversation has gone up a notch and the question on everyone’s mind is which country will beat all others to vaccinating its people and getting back on its tracks.

Israel is not sitting idle and has already reportedly signed deals to acquire vaccines from Nasdaq-listed biotechnology companies Moderna Inc.and Arcturus Therapeutics Inc. as well as from its own Israel Institute for Biological Research. While the institute claims it already has a product and will begin clinical trials in October, Moderna is estimated to be at the most advanced stages of developing the vaccine. Arcturus has recently started the second phase of clinical trials and has signed an agreement with another government to sell its vaccine. Israel is also reportedly in advanced negotiations with British-Swedish company AstraZeneca PLC, whose vaccines have now entered the third stage of clinical trials.

But, you may ask, why go through the trouble of securing these agreements when the vaccines are not yet approved for use and many other countries are sealing similar deals? According to Uri Lerner, the scientific director of Midaat, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing public health through preventive medicine, once a vaccine is approved for use it will be impossible to come by. “If Israel can secure in advance even just 1 million doses it could mean the difference between a functioning health system and a collapsing one,” Lerner told Calcalilst in an interview.

Related Stories

“There is, however, a pretty good chance that none of the companies currently conducting clinical trials will make it and then it will turn out we bought a pig in a poke with money that could have been used to improve our healthcare system,” Lerner added.

The closest race for developing the vaccine is currently between three companies—Moderna, Pfizer Inc., and AstraZeneca. All three are putting a lot of their efforts into increasing production capabilities but, according to their own numbers, it is quite clear that there will not be enough vaccine doses to go around any time soon. This fact is what instigated the current arms race, with wealthier countries willing to pay a fortune in advance, despite the risk of throwing money away, should the trials not pan out.

Poorer countries are forced to rely on the generosity of philanthropic organizations, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which promised to fund vaccines to third-world countries; develop their own vaccines; or attempt to steal information, as it appears North Korea has been doing in a series of cyberattacks against the west.

Right now, there are two types of future vaccine acquisition deals. The first, as exemplified by the agreement between the U.S. and Pfizer, is low risk. A government places an order for a specific amount in advance with payment upon delivery. This means that should the company not be successful in clinical trials and the vaccine receives no regulatory approval, the deal would be called off.

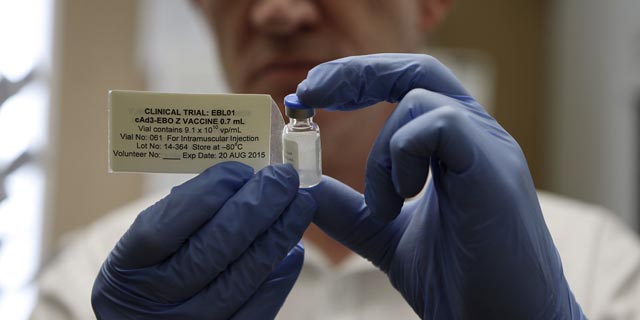

Lately, a new sort of contract emerged as companies realized that while their product is in high demand, accelerated clinical trials are expensive and the money needs to come from somewhere. And so, the option contract was born, with governments paying some of the money in advance receiving a commitment to provide the vaccines once regulatory approval is received.

The Israeli Ministry of Health was unwilling to disclose what it paid per its already signed agreements but, based on the sums the U.S. government released, it was likely less than $100 million, a relatively menial sum for Israel, especially compared to the cost of over 1 million unemployed citizens. One executive from the Israeli biomedicine sector who spoke to Calcalist on condition of anonymity estimated that if and when a U.S.-manufactured vaccine is approved, the administration would forbid its export for at least several months until it can secure enough doses to protect its own citizenry. It is likely, however, the executive added, that countries that already have a signed official contract with the manufacturer, could circumvent this restriction.

At the end of the day, it is a matter of risk management, Erez Garty, an immunologist and the head of science communications at the Davidson Institute of Science Education, told Calcalist. “I would like to hope that the governments are taking precautions with these contracts,” Garty said.