Combat vs. Tech: Does your IDF service determine your future?

While many Unit 8200 recruits set themselves up for lucrative jobs, high tech leaders that served as IDF fighters say they would not change a thing

The Israeli satire and skit television show Eretz Nehederet, which created countless household characters and catchphrases since its first episode almost 20 years ago, took that question and in a one off-handed joke ignited reactions on social media. In past weeks, through a series of skits starring comedian Udi Kagan, the show has been touching on one of Israeli society’s most recent and glaring friction points - the high tech industry vs. the rest of the country. On the show’s 19th season Kagan plays the role of a CEO of the fictional high tech company WEBOS, placing, what some will say, an extreme mirror in front of the local ecosystem, perhaps mocking it, perhaps displaying envy towards it.

In a recent skit, lampooning the race for human capital in the industry, the CEO is waiting outside the base of Unit 8200 (which became over recent years the umbrella term for the IDF technological units), hoping to recruit (maybe even kidnap) talents before they enter the job market. A vigilante soldier recognizes the scheme and runs away from the car, before a combat soldier walks by asking for a ride. The CEO asks the soldier where he serves, “Paratroopers” the soldier answers and the CEO closes the car's window before going on to search for even younger talent in an elementary school.

This one joke, from a seven minutes segment, spakred emotions and prompted many former combat soldiers who work in high-tech to comment, criticize and even offer help to other combat soldiers who wish to enter the industry. Taking the discussion further, CTech spoke in recent days with a few industry leaders who did not take the technology units’ route during their service and asked them about how their military experiences helped shape their careers and whether they see a difference between combat and intelligence soldiers in the workplace.A battle in Lebanon fuels a startup 30 years later

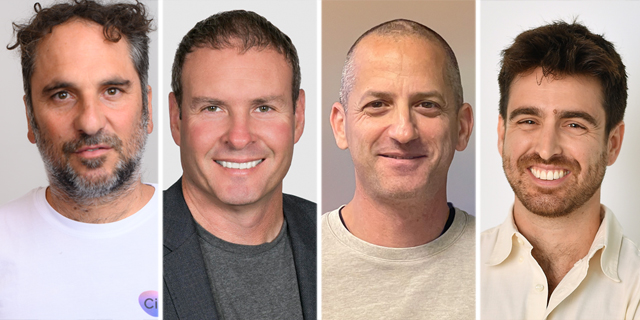

“As a commander, especially in combat, you must be very disciplined, but the soldiers are constantly on edge and you have to be able to manage that as well,” said Irad Eichler, founder and CEO of Circles, an online platform that brings people who need support together. Eichler (46) started his military service in the early 90s at the Combat Engineering Corps but after he graduated his officer training, he eventually became the chief aid and head of security for the commander of the Lebanon Liaison Unit, a brigade that was responsible for the IDF’s presence and actions in southern Lebanon for 18 years. “Our brigade was inside the South Lebanon Security Belt responsible for the first line of defense against Hezbollah. We were inside a war zone, and we had to move undercover within it, and I was leading the commander’s security team,” he recalled. “For me, my military experience shaped the way I look at and consider responsibility. Meaning the way I try to be proactive and accountable to the things I do, I do not think I could manage my work in the way I do without my military experience.” “I had one soldier who was extremely talented but also very wild. We are still friends, but my skill to send him to do things while also setting boundaries for him really shaped him as a person, and helped the team. And it is the same here, I have the best team with the best people I would like to have, they are super talented and are testing boundaries, my boundaries and the boundaries of reality, making the impossible possible,” he added. “In the IDF the officer eats last, sleeps last. Whenever I was given a treat or a fun training I passed it along to my soldiers,” he said. “And it is the same here, to get people to work with you and follow the path you set they need to know that their welfare comes before yours.” Eichler’s venture, Circles, creates online groups of people dealing with similar challenges and guided by a professional. “We are solving the challenge of loneliness for people that are dealing with any kind of challenging life event, grief, separation, divorce, caregiving, and so on. The way we solve it is we connect people in small groups of similar people dealing with the same life challenge and together they go through the journey. In essence, we are restructuring social support systems in society,” he explained. “I went through a lot of experiences in my life, army-wise and not in the army, which were emotionally challenging and my natural instinct was not to share with other people,” he said. However, the most notable thing perhaps during the conversation with Eichler was the fact that at the beginning he highlighted his mother’s battle with cancer as the trigger that led him to form Circles. “I saw how lonely she was, and she told me that even though I am with her she feels lonely. That I do not really get what she is going through. And two days after that I overheard her speaking with a friend who also had cancer and my mother was vivid and alive in that conversation.” But as the discussion shifted to his military background, Eichler shared a story about a difficult incident that took place in southern Lebanon and included an enemy ambush and a shootout, which could have sowed the first seed for Circles, more than two decades ago. “According to the military, it was a successful operation. We had a debrief that night, and the brigade commander Eli Amitai asked us to talk about how we felt, which only now I understand how meaningful that was,” Eichler said. “What we do in circles is help people so they do not have to deal with their trauma by themselves. So at the most strategic level, you can tie the company to this extreme experience I had.” “I want other people to be able to talk about what they are going through because I know it will help them,” he concluded. “If they are good, they will catch up” “It is not one event or skill that you learn during your military service, it is an entire package that at the end of the day gives you the ability to really be confident in the fact that you can persevere through tough situations, so when they come, not just in business, you will have the confidence to push on,” said Marc Gaffan, CEO of Hysolate, a cybersecurity firm focused on end-points protection, and a self-proclaimed “techie at heart.” Gaffan (49) served as a fighter at a top infantry unit, and like many of his generation, spent a big portion of his time in neighboring Lebanon. “I was recruited in 1990, so a long time ago, and I was in the Golani Brigade’s reconnaissance unit. I served there for three years, which was very intensive mentally and physically. Those were the days the IDF was deeply involved in Southern Lebanon, I spent many days and weeks inside bushes. So it was very exciting, challenging, and I think rewarding service,” he said. Despite being given the opportunity, Gaffan decided not to become an officer and chose to continue serving within his unit. “Not everyone who goes to the officers’ course returns to the unit, most of the brigadiers in Golani saw the reconnaissance unit as the incubator for the Golani Brigade’s leadership. So not everyone got to come back after the officers’ course.” When asked if he saw a connection between the way he described his old military company, and how some of his old workplaces, mainly Cyota, which was co-founded by Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, grew talent, Gaffan agreed there is some similarity. “If you look at the senior management team at Cyota, Michal Tsur co-founded Kaltura, Michal Braverman-Blumenstyk went to Microsoft, Amir Orad is the CEO of Sisense, and Lior Golan is the founder and CTO of Taboola,” he pointed. “People that experience success and excellence essentially have this blueprint of what it looks like in their head. When you have a blueprint of what it looks like it is a lot easier to go and chase it.” It seems that this approach rings true in Gaffan’s mind also when discussing military service and the local tech industry at large. “People that go to elite units are super motivated, you cannot survive there without a high level of motivation, perseverance, and grit. So to begin with, you get people that are overachievers or are super motivated, that want to excel at what they do,” he said. “And it is not just dealing with the physical side, it is complex situations, in combat, dealing with hardship, with team dynamics,” Gaffan explained. “Building a business is a rollercoaster. There are lots of downs and you need to deal with a lot of failures. It is part of the deal of how you get up from hardship or failure and go on to the next thing and punch on and keep your spirits high.” During the conversation, Gaffan did not only speak from the CEO and a former combat soldier’s perspective, but rather as a father whose oldest daughter serves as a combatant in the Artillery Corps. “She could have her pick, she passed on every single technology unit that knocked on her door because she wanted to be a fighter,” he said proudly. “She just started commending new recruits, and those are challenges. Those are challenges of ‘ok, it is my first time I am responsible for a bunch of kids, what do I do?’ And a week into it she says ‘ok, I am doing well,’ and that can give you a lot of confidence, which is a key thing in life.” But when speaking again as someone from the industry providing advice to his daughter or any other future soldier, Gaffan is adamant that if they are good enough they will find themselves on their chosen path regardless of where they served. “If they are good, if they were talented enough to go to an elite technological unit but they went through the non-technological route, they will catch up,” he said. “When you look at the course of an entire career, those who do not go to the military in a tech capacity but have got it in them, within three, four, five years they catch up. And I think that after that, what they accumulated in their military service pays off in terms of leadership.” From gaming to tanks to 3D ”What I am saying might not be statistically significant,” said Gilad Talmon, CEO of TetaVi, a company specializing in volumetric video. “Except for very specialized areas, it does not matter what you did in the military. It matters what your capabilities are, it matters to some extent what you studied, and what you have experience in. I have seen people who were in Golani, Givati, Navy, or whatever succeed in high tech and I have seen people who were in technological units failing completely.” Talmon started his military service in the Armored Corps in the 90s, later becoming an officer, and moving around between several units. His last rank while in active duty was Lieutenant, however, now he is Major in the reserve service. As a high school student studying advanced physics, math, chemistry, and English, he was offered to try out for several technological and intelligence units, “the Talpiot program, which was the only one of the bunch I applied to did not take me before I signed up to go to combat duty,” he recalled. But even in the Armored Corps, his technological incline found its place. “Early in my training, I became a tank’s gunner, before becoming a commander and later an officer. I was at the tank simulator, and I had been a gamer forever, that is also how I got to TetaVi. I grabbed the joystick and I moved it around, placed it on the target and, fired, made a correction, again fired, again and again, and the operator looked at me and said ‘you are making it look easy,’ and I told him ‘yeah because I’ve been holding a joystick since I was six’ with the first Atari.” These days Talmon is hitting different targets as his company recently hired two former Warner Bros. Entertainment executives on its way to deliver engaging content into the metaverse. “Volumatic video is essentially the only way to bring video content into the metaverse’s 3D environments because the video is modeled in 3D so it lives in a 3D environment,” he explained. “We work now with some of the biggest names in Hollywood and the music industry to bring them into the metaverse. And we are developing something that will come out towards the end of the second quarter, beginning of the third quarter next year, that is an application that will allow user-generated content in volumetric video.” “When we recruit people I do not care where they are from, we do not look if it is 8200 or Talpiot or wherever,” Talmon continued. “Our head of engineering worked in advanced IT in the military, and he is an algorithm designer, one of the best 3D visual algorithm designers in the world. Our chief of algorithm has a master’s in mathematics with a dissertation that she completed with distinction as a school teacher in the military.” When asked about his personal experience in the military and what he took with him into the industry, Talmon recalled that a few weeks into his basic training he wanted out of the Armored Corps. He called his father who had the connections to pull him out and move him somewhere else but refused. “He told me to tough it out, suck it up, and do it. And I did. That stayed with me in the sense of ‘if other people can manage it, you can manage it,’ and I think that helps a lot in a startup environment and high tech environment. I think that is something relatively unique for the Israeli high tech environment.” “Sometimes tenacity is the only difference between those who succeeded and those who did not. For me that is something I developed during my military service,” he concluded. “Builds character and gives you the feeling you can accomplish anything” “Usually, when we meet with startups, we see the ‘Team’ slide and on it are all the logos of where they previously worked and served, and I think 90% of the time we will see the Intelligence Corps logo,” said Tal Zackon (30), Principal at F2 Venture Capital. “When talking about combatants, I think that both myself and Jonathan Saacks, our managing partner, kind of have a soft spot for those kinds of founders.” Zackon, a former fighter in an elite unit, can offer some insight on the discussion from the investor side of things. He has been with an early-stage fund almost since its inception four years ago, explaining they are “usually the first institutional money that goes into a venture, check sizes are up to $5-$6 million as we lead or co-lead the rounds. We focus on B2B, SaaS, technology companies.” For him, sitting across the table from entrepreneurs, the fact they served in a combat unit, helps him better understand them. “In my eyes, and of course, I am biased, when I see founders from one of the combat units, and I see them building a company that is technologically oriented, it gives, in my opinion, a strong validation to what kind of people they are because I know what they have been through and if they got themselves to build a tech company even though there is such competition and possibly more quote-unquote qualified people in the ecosystem,” he said. “For me, it is about character and being relentless,” he continued. “Building yourself up inside an ecosystem that is not always as accepting and getting to a stage you feel comfortable in to build a tech company shows character for sure.” Zackon also discussed his personal experiences and how they helped him get where he is today. “What I got out of it, and it is something I think about a lot, is that any time I encounter some kind of challenge, competing on a deal or some kind of crazy deadline, I always think to myself ‘I have done things that are way more challenging in my life,’ I mean we have done some crazy things no one can imagine and if we pulled those off, I think some of my day-to-day in high tech and work seem like a walk in the park. I know for sure it builds character and gives you the feeling you can accomplish anything.”