A Look at China's Multi-Billion Dollar Live-Streaming Industry

In China, live-streaming has become a mass phenomenon. Considered one of the country’s most popular forms of entertainment in the past few years, its socio-cultural impact is immense

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

Live-streaming was created and developed in the West. It is usually one of many features in popular social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube, though Amazon’s Twitch is dedicated solely to this feature. In China, however, live-streaming has become a mass phenomenon. Considered one of the most popular forms of entertainment in the country in the past few years, its socio-cultural impact is immense.The app I was using is one of several live-streaming pioneers in the country. Its developer, Guangzhou-headquareterd YY Inc., listed on Nasdaq in November 2012 at a valuation of $600 million and is currently being traded at a market capitalization of $5.6 billion—more than nine times higher, in just six and a half years. In its fourth-quarter report for 2018, YY stated it has 90.4 million monthly active users, 8.9 million of whom are paying customers, who generated 15.7 billion yuans (approximately $2.29 billion) in revenues for the company in 2018.

YY is just one of hundreds of live-streaming apps and websites operating in China, including Kuaishou, Douyu, Meipai, Inke, and Momo, which together form a lucrative industry. In a recent report, Shenzhen-based market analytics firm ASKCI Consulting said it expects the live-streaming market in China to be worth 74.55 billion yuans (approximately $10.84 billion) by the end of 2019 and 86.63 billion yuans (approximately $12.6 billion) by the end of 2020, more than double its worth in 2017.

These remarkable numbers are a result of one unique feature within the Chinese apps. As soon as Xiao Yu starts to sing, I notice something I have never seen before—digital gifts, including lollipops, flowers, perfume bottles, and even a diamond ring, begin to pop up with the usernames of benefactors flashing for several seconds on the screen. I soon realize these are gifts bought for the host by users at costs ranging from several cents to dozens of dollars. During a particularly beautiful verse, Xiao Yu is showered with about 50 clapping hands simultaneously.Xiao Yu thanks her benefactors personally, sometimes urging them to be more generous. “Mind you, it is very late at night and I am working very hard,” she says playfully. “Where were you yesterday?” she asks, half-inquiring, half reproaching a regular who had just logged in. He quickly apologizes, pinning his absence on a busy work schedule.

I decide to join in on the party. In order to hand out gifts, you must first convert money into app tokens. 1 yuan (approximately $0.14) is worth 0.7 YY tokens. I buy a box of chocolates priced at 6.9 tokens, wait for the perfect timing, and send it to Xiao Yu. “Thank you so much, Afei,” she calls me by my Chinese name, and, strangely enough, I do get a little excited.

In the middle of the night, YY’s app is full of active live-streaming rooms. Most of the hosts are women, but I also find a group of men having a lively discussion during a late night dinner at a restaurant, and one male host roaming a busy street in Thailand. I move from one girl demonstrating how to braid hair to another that is dancing sensually, and then to a third, who is playing with her dog. It reminds me of old-fashioned peep shows or a more professional version of Chatroulette, a website that was extremely popular for several months in 2010 that randomly connected strangers for video chat sessions.

Young people in China deal with severe loneliness as a result of the swift social and economic changes the country has undergone in recent decades, Film documentarist Hao Wu said in a recent interview with Calcalist. Wu’s latest film, “People's Republic of Desire,” provides a window to the backstage of the Chineses live-streaming industry. A lot of young people have no siblings due to China’s now-defunct one-child policy, and they see live-streaming stars as their brothers and sisters, he added.

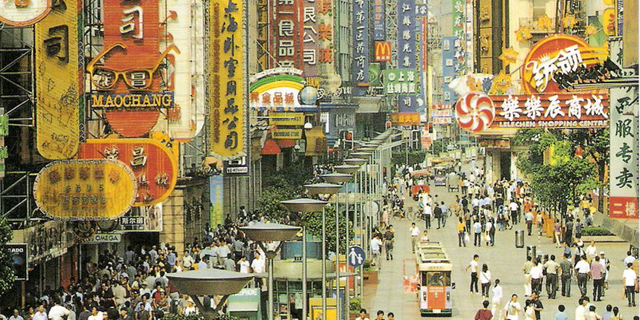

The growth of the Chinese economy gave young people from rural areas a chance to travel and see new places, but they find themselves in huge alienating metropolises where they feel out of place, Wu said. These people are often uneducated and unskilled and have no feasible way of climbing the social ladder, he explained, and this sense of being stuck just reinforces their sense of loneliness. For some, live-streaming is a type of escapism, but the more time they spend online, the more alone they feel in the real world, he said

It has been several weeks since I first watched Xiao Yu, and she has since completely vanished from the app. While disappointing, this was not surprising. It was clear that Xiao Yu was just a small fish in the Chinese live-streaming industry. The gifts she collected during her broadcast—a few dozen dollars-worth—are proof of that. When real stars go on air gift spaceships, sports cars, and speedboats—priced at hundreds and thousands of yuans each—rain down.

The app gets between 50% and 60% of the cost of the presents, and the rest is shared between the host and their agent. Behind almost every host—big or small—is an agent that trains them to milk their viewers to the fullest extent, helps promote them, and secures them a prominent spot within the app.

Live-streaming has become, in a way, the embodiment of the Chinese dream of fame and fortune. However, like many web phenomenons, only a very select few of those involved with it actually reach the desired prosperity. According to a survey released in early 2019 by popular app Momo, just about 21% of full-time live-streaming hosts earned more than 10,000 yuans (approximately $1,450) a month. Only the biggest stars, those who last longer and manage to maintain a flock of millions of loyal fans, can turn live-streaming into a lucrative source of income.

Before becoming one of YY’s biggest stars, racking in $40,000 in gifts every month, Man Shen, one of the hosts featured in Wu’s film, used to work as a nurse in her hometown Chengdu in southwestern China, earning 24,000 yuans (approximately $3,490) a year. Like Xiao Yu, she also sings in her bedroom, spicing things up with dirty jokes and tales of the plastic surgery procedures she has undergone.

Xanliang Li (Big Li), another star of Wu’s film, was born poor and came to Beijing at age 16 to work as a hotel security guard. He later became a comedian and a live-streamer making $60,000 a month through digital gifts. While on the air, Big Li jabbers about current affairs and the joys and woes of his rags-to-riches story.

Video blogging, better known as vlogging, never really took off in China, Wu said. When it was booming in the West about a decade ago most web users in China lacked the necessary equipment to create good videos, so very few could actually make a living off it, he explained. Online advertising was also far behind in China at the time, so even those who became stars didn’t really have a way of making money, he added.

Both Shen and Big Li seem to have made it in the highly competitive world of live-streaming, but Wu’s film reveals some of the less-glamorous parts of their lives. Ahead of the annual YY contest, in which they must raise millions of dollars from fans in order to win first prize, Shen and Big Li’s pleas for donations become almost desperate.

Live streaming stars are also forced to deal with trolls and abusive comments. In one scene, Shen is infuriated by a user calling her a whore. In another, Big Li bursts into tears as fans accuse him of wasting their money by losing the contest.

Related stories

A male live-streamer has to be perceived as an Alpha-male, a born leader, an ideal drinking buddy, so trolls will attempt to present him as a cheater and a fraud, Wu said. Women, on the other hand, are expected to sell a certain type of sexuality and so trolls will choose to attack their physical appearance or accuse them of sleeping with fans, he explained.

Shen and Big Li both stay home most days, corresponding for hours with their most generous benefactors, which are responsible for 80% of their total income. Such big spenders, known as tuhao—a Chinese slang word for nouveau riche—spend tens of thousands of yuans a month on premium subscriptions that award them with royalty crowns or duke titles within the app, and hundreds of thousands of yuans more each month on gifts for their favorite hosts.

Being a tuhao is in itself a way to gain attention and appreciation from the audience—the biggest spenders are consistently listed in a chart at the top of the screen and all users are immediately notified when a king or a duke enters the same “room” as them.

Big spenders also expect, and normally receive, special treatment from hosts, which could include long private chats and dinner sessions. Shen, like many female hosts, often finds herself having to deal with sexual propositions from her heavy backers. After not visiting the app for a while, I began receiving emails from YY claiming one of the female hosts I watched “misses me” and wants to “go on a date,” emphasizing the sexual aspect of this type of voyeurism.

Manufacturing and distributing pornographic materials is strictly forbidden in China and is considered a form of “spiritual pollution” by the regime. In October, a court in the Yunnan province in southwest China gave a six-month prison sentence to a person who managed a WeChat group in which pornography was shared.

Despite the regime’s obvious disapproval, in a survey published in 2015 by sexuality researcher Suiming Pan, 79% of Chinese men and 51% of Chinese women reported they have watched pornography during the previous year, proving that a thirst for such material exists. Live-streaming is there to satisfy some of it, without any type of nudity.Some of this thirst can be attributed to the fact that China suffers from an acute imbalance in the number of men and women. According to data provided by the Chinese government, China has a surplus of 33 million males compared to females. Estimates in the West speak of much larger numbers. This abnormality is largely attributed to decades-long limitations that allowed Chinese parents to have only one child, driving many parents to abort female fetuses or abandon or give up newborn girls, due to a cultural preference towards male descendants. The “shortage” in potential female mates drives some men to search for substitutes within the digital realm.

Wu, a native of China who immigrated to the U.S., worked for web companies such as Alibaba and Yahoo before turning to documentary filmmaking in 2005. In 2006, he was detained in China for five months while working on a documentary on underground Christian churches operating in the country. In 2014, a friend directed his attention to YY’s stock and he began to look into the company.

Released several months ago, his film uses live-streaming to reflect on contemporary culture’s obsession with money. “It’s all bullshit,” Shen says at one memorable moment in the film. “If you have money, people worship you, and if you don’t, then nobody knows who you are.”

Wu said that at first he thought live-streaming was just another fun internet phenomenon and did not realize what a major role money plays in it. Western celebrities such as the Kardashians make their money off commercials so it remains a lot more subtle, but with live-streamers, the exchange is much more direct, he explained. Just talent is not enough to make it in the world of live-streaming; a host must have wealthy patrons that buy them expensive gifts because that is what regular fans want to see, Wu said. To see someone else spending is also a form of entertainment, a sensation, he added.

The film also follows the fans on the other side of the equation. The average fan spends 7.2 hours a week watching live-streaming, according to a 2018 study by Chinese born researcher Zhicong Lu, a PhD student at the University of Toronto. Unlike the tuhao, the vast majority of Chinese live-streaming viewers dubb themselves diaosi, a slang word for losers often used to describe those who do not have a shiny career or a promising future.

Diaosi are normally young people who moved from rural areas to big cities in order to find manual labor. They have little to no formal education and spend most of their free time watching live-streaming, spending a significant part of their insignificant pay on virtual gifts for their favorite stars.

Reports of young live-streaming fans that get themselves or their parents into financial troubles have become a common occurrence in recent years. In December 2018, a 24-year-old called Liu disappeared from his home in Changsha in central China along with 1.7 million yuans (approximately $247,000) of his parents’ money. Liu, described by family members as an introvert who hardly left the house, spent at least a third of the sum on YY’s app, paying about 12,000 yuans (approximately $1,743) a month on a premium subscription and the rest on digital gifts to hosts.

One month prior to Liu’s disappearance, local media reported on another 19-year-old who spent about $40,000 on gifts to one specific female host. “I was very excited to log on to the app and have people call me ‘sir,’ as if I were super rich,” he told reporters at the time.

In January, a Beijing court ordered live-streaming app Inke to refund 400,000 yuans (approximately $58,000) to the mother of a 15-year-old girl. The mother had sent her daughter to school in Canada and provided her with access to her AliPay account. Instead of using the account to pay for her daily expenses, the daughter spent hundreds of thousands of yuans on gifts to a particularly attractive male host. Inke failed to block the payments even after the mother informed them her daughter was underage.

It may seem strange that fans spend so much money on buying celebrities gifts when they can view the content for free, but according to Wu, since these stars have tens of thousands of fans watching them every night, the only way for fans to catch their attention is to pay.

Unlike other types of celebrities, live-streamers often come from backgrounds that are similar to those of their fans, so their viewers are trying to live vicariously through them, Wu said. Because they identify with them so completely they want to see the hosts succeed and become rich, and that is why they are willing to give them their money, he explained.

Since Wu finished filming his documentary in 2016, live-streaming has continued to grow, reaching new audiences and expanding its array of hosts to include not just pretty young women but also elderly people using the platform to gain some attention and extra cash. Among the more extraordinary hosts are 39-year-old Haicheng Tian, a former manual laborer who lost both his hands, and his six-year-old daughter, who broadcast together to 450,000 followers from their home in northwest China, making about 4,000 yuans (approximately $580) a month.

In the past two years, live-streaming also achieved a foothold in another vibrant industry in China—online shopping. Alibaba’s Taobao live-streaming app offers no digital gifts. Instead, it shows hosts walking through shops in China and abroad, trying out clothes and jewelry, and selling practically anything—from puppies to traditional Chinese medicine. Think of it as a shopping channel on steroids.

According to Alibaba, in 2018 live-streamers on its platform made the company 100 billion yuans (approximately $14.5 billion) in sales. Surprisingly enough, the biggest stars on this platform are farmers filming themselves in their corn fields or chicken coops. The best earners on the platform so far were farmers from the Hunan province in central China, who managed to sell 2 million kilograms of oranges in just 13 days through live-streaming.

As is the case with other web phenomenons, competition over attention tends to encourage sensational practices by live-streamers—from hosts filming themselves having sex to those attempting suicide on air. In February, a 28-year-old called Li jumped to his death from a bridge in the Zhejiang province in eastern China. Li dreamt of quitting his day job as a cook to become a star on live-streaming app Kuaishou. To achieve his goal, he attempted to impress fans by jumping off the bridge and onto the river below, which turned out to be too shallow. That same month, a 29-year-old live-streamer called Chu died after gulping an entire bottle of an unknown alcoholic beverage in one sitting. In the past, Chu, who made about $74 in a day’s broadcast, also drank a whole bottle of cooking oil, at the request of viewers.The growing popularity of live-streaming and some of the sensational headlines associated with it have brought the Chinese government to attempt regulating this new form of entertainment. Over the years, the government has shut down dozens of live-streaming platforms and tens of thousands of accounts it deemed damaging.

Latest regulations require live-streaming platforms to allow users to report violating content on a 24-7 basis and to remove infringing accounts within just 90 seconds from the moment a report was filed.

In 2016, China went as far as to forbid seductively eating a banana on air. In January, the Hebei province in the country’s north issued new regulations forbidding live-streamers from wearing sexy clothes, including see-through dresses and skin color leggings, as well as clothes portraying the Chinese flag or other national symbols. The subject of Chinese national symbols on live-streaming platforms has been under increased scrutiny ever since last year, popular 20-year-old host Yang Kaili was detained for five days after singing the Chinese anthem while mockingly waving her arms in the air. Despite apologizing for the segment, which only lasted a few seconds, Kaili’s channel was permanently removed from the platform.

No Comments Add Comment