“A coalition of hate”: The online extremists that are testing Big Tech

Hate speech has been bubbling on social media and the internet for decades - but it all came to a climax this month at the heart of America’s democracy

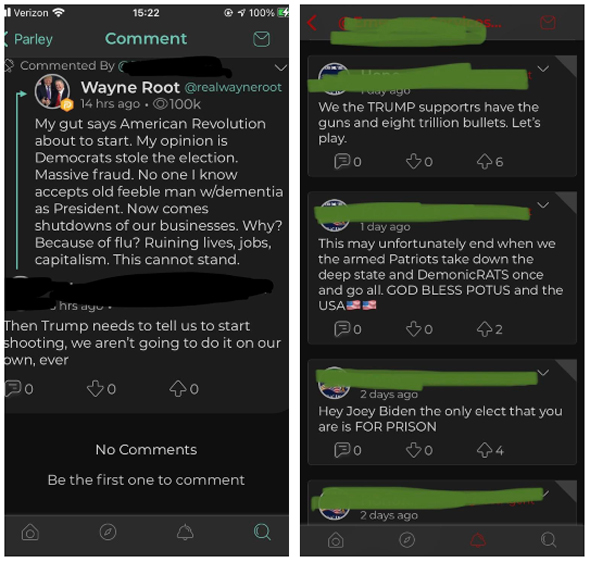

A common thread among those who marched in the name of hate and perceived injustice was that they would meet in fringe online communities hosted on platforms such as 8Chan or Parler. These platforms, that pride themselves on enabling free speech and unfiltered communication, are allowing users to “cross a red line” from hate speech to terrorism and inciting violence - something that Professor Weimann explained is a new trend in his research.

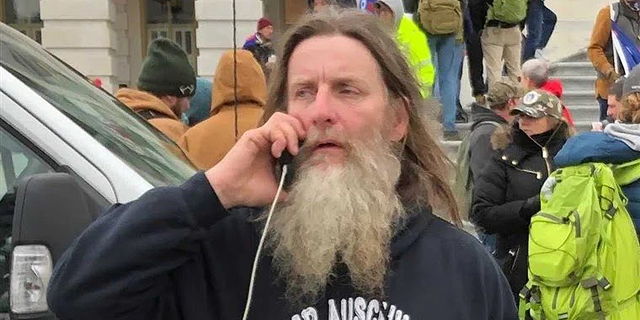

“For many years, I was studying online terrorism. Our definition of terrorism includes the threat of violence. Violence had to be part of it,” he said. This means that, for the decades of research, his threshold of hate speech and inciting acts of terrorism relied on the call for violence and not simply words that some found offensive. As years went on, those goalposts began to shift and rhetoric became more intense and hateful, particularly as access to online discussions became easier than ever before. Today, social media platforms have evolved to become the online equivalent of public squares where citizens can engage in free and open dialogue - sometimes leading to deadly results. “In the last few years things have changed, because those groups that enjoy the freedom of speech or pushed people to the edge, crossed the red line, and once they started shooting people in synagogues, mosques, and now Capitol Hill, it became clear that you are looking at domestic terrorism.” The Capitol Hill riot and its tragic consequences resulted in the second impeachment of President Trump after Congress charged him with ‘incitement of insurrection’. However, Professor Weimann believes that the actions taken that day were long in the works, and perhaps had been planned for some time. “The online platforms and social media played a crucial role in forming, in channeling, and uniting these groups and finally directing them to the same place to take this chance to be violent,” he said. “All these calls to shoot, and fire, and be violent were all there. And not just on the last day. It was there for weeks. It could be identified… the alarm bells were ringing but nobody listened.” One week after the riots, CNN reported that investigators were pursuing signs that the attack on the Capitol had been planned in advance, only hours after the impeachment had already taken place.For years, social media companies and Big Tech have been put under pressure by advocacy groups that hope to curb some of the violence and hate speech they allow on their platforms. Facebook and Twitter banned Holocaust denial on their platform as recently as October 2020 - and yet three months later a man wore an Auschwitz sweater at the front gates of American democracy. Even as social media companies rush to recategorize Holocaust denial as hate speech and finally remove some of the images and hashtags that plague online forums, for Professor Weimann it is a futile gesture.

“The idea you can block the voices of hate and drive them away is a naive one,” he told CTech. “Anyone who thinks Facebook removes them and Twitter removes them and then they’re safe, is naive.”The spread of hate online goes beyond the hate speech that runs rampant on their platforms, but in the goods and services that can be purchased online, too. After the image of the Auschwitz sweater went viral around the world, the ADL (Anti-Defamation League) and the World Jewish Congress (WJC) called on companies that operate online marketplaces to “strengthen and better enforce policies banning any product that promotes or glorifies white supremacy, racism, Holocaust denial or trivialization, or any other type of hatred or violence.”